Literatures of dementia, Alzheimer’s and memory loss.

Interview by Óscar Ortega Montero for Safundi, September 2025.

OO: I wanted to ask: do you still keep that tennis racket?

HT: Yes, I still have the tennis racket. It’s actually in my office here.

OO: The tennis racket reminded me of the idea that memories are codified in objects, right? I’m asking this because I found striking, if that’s the right the word, that you said in your piece that you were struggling to remember your mother’s voice. This made me think whether or not you feel you can still play her voice in your mind.

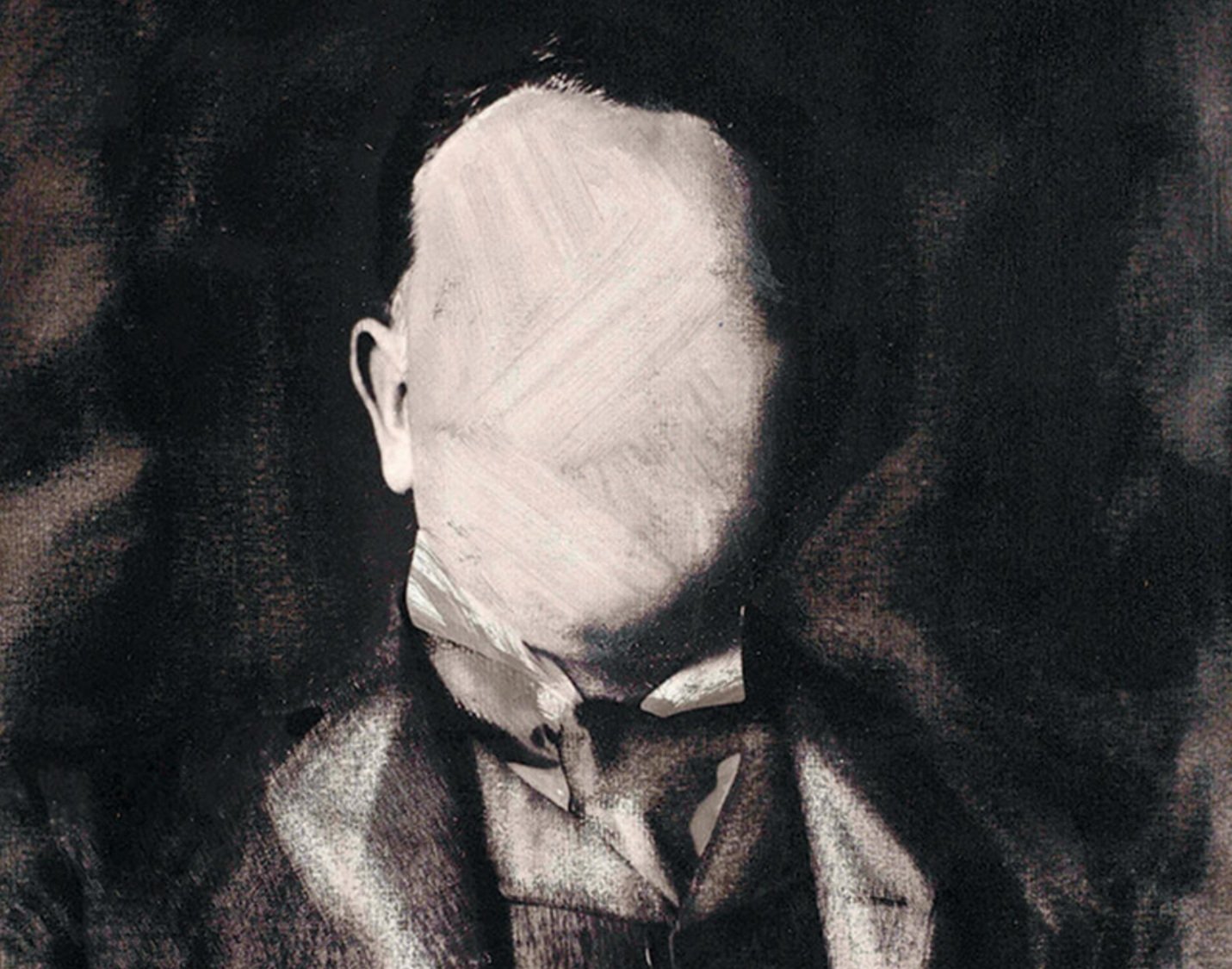

HT: It takes you into the whole phenomenology of what it means to remember, what is happening in our brain when we do. When we remember something, to what extent are we accessing a memory trace? To what extent are we overlaying it and reconstructing it in mind of our later experience? I mean it is a somber fact that I can’t play my mother’s voice in my mind even though at the time I was always recording things. I’d play the guitar, I had a four-track recorder and yet at a time when the world was beginning to record everything on devices, I don’t have any record of her voice. I don’t have a recording of her voice so I can’t remember it vividly.

OO: The aesthetics of remembering are complex, and the way memory works, too. I believe voice is something we strive hard to preserve in our minds, as is the way someone who is no longer with us is present. When I think of my parents’ voices this helps me feel peace inside myself. I’m short of words to describe that feeling.

HT: Voice is such a complicated idea, isn’t it? Because you have the sonic quality, but then you also have the metaphorical quality. On the other hand, my mother’s voice, understood as her approach to the world, her way of phrasing things or her way of being with me, I feel I remember it very powerfully. I’m trying to preserve it, I’m trying to honour it, and I’m trying to bring it through my body and my writing into this piece. So her voice is thus present, even though I can’t remember it, it’s the paradox.