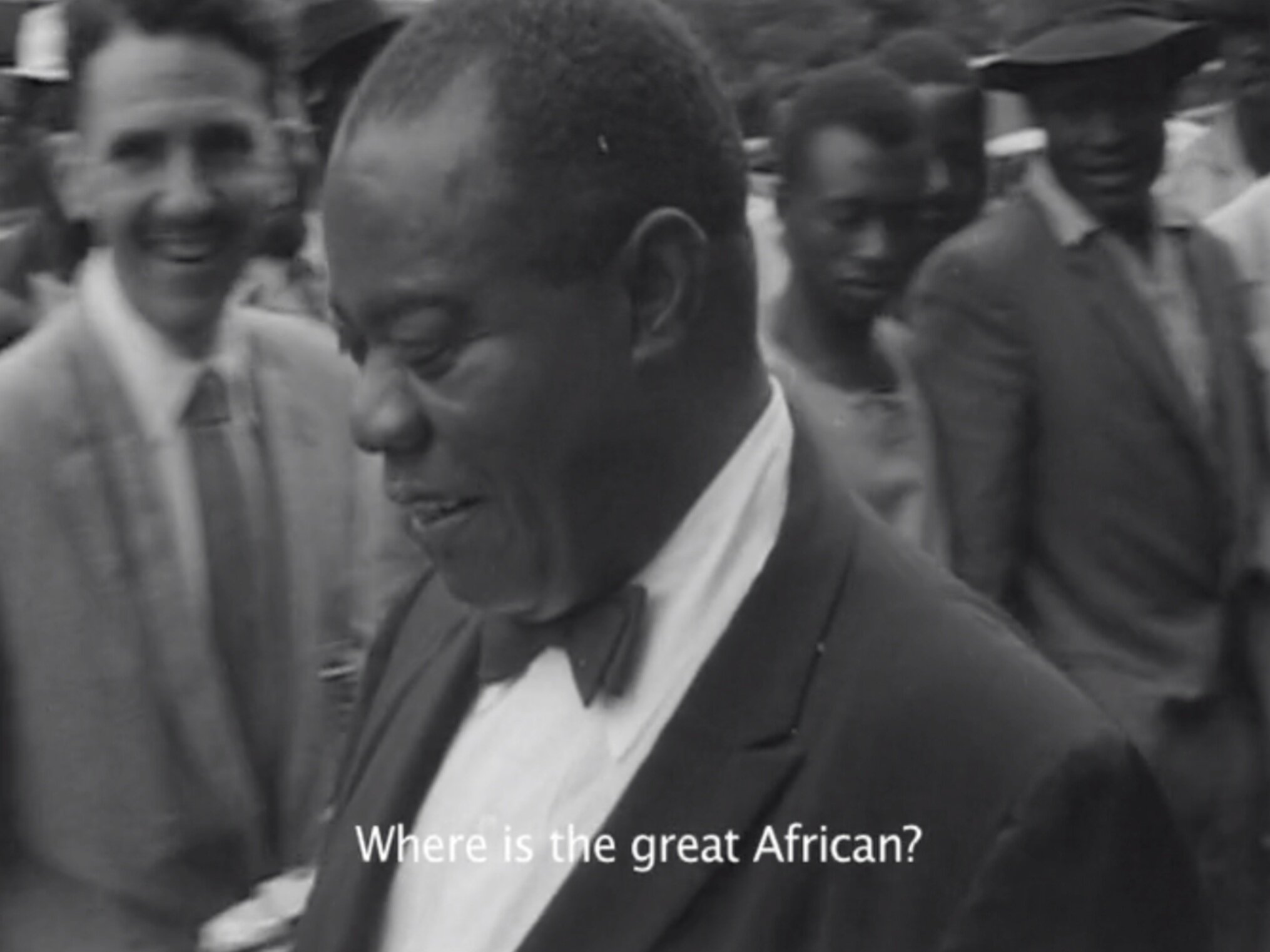

When Louis Armstrong met August Musarurwa.

Anybody Can, in Your History with Me: The Films of Penny Siopis, ed. Sarah Nuttall (Duke University Press, 2024).

“Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around. That’s what you hear vaguely in Louis’s music.”

1.

The African Dance Band of the Cold Storage Commission of Southern Rhodesia – it was the band with the longest name in the world. The words appear as faded images flicker across the screen: tobacco auctions, tourist cruises on the Zambezi river. A languorous saxophone plays.

So begins Penny Siopis’s ‘Welcome Visitors!’, a filmic reimagining of the life and music of August Musarurwa. Musarurwa was a bandleader and saxophonist who learned the instrument while working as a police interpreter in Bulawayo in the 1940s. The torrents and cataracts of the Zambezi keep unspooling as we hear the tune that made him famous: ‘Skokiaan’. The crackle of old vinyl joins the mottled footage – of farm labour, dance performances and colonial officials with awkward body language – and the original begins to play. Some quick-strumming banjos mark out a carnival rhythm, then comes a long, bending note on Musarurwa’s sax, sliding down to a riff that everyone knows.

‘One day a European came to record Skokiaan’. This was Hugh Tracey, a British-born ethnomusicologist intent on capturing indigenous sounds as far afield as Uganda and Katanga for his International Library of African Music (a bit like Alan Lomax in the American South, amassing field recordings for the Library of Congress). Despite his disdain for ‘foreign inspired trivialities’, Tracey also doubled as adviser and talent scout for Eric Gallo, whose label was based in Johannesburg but often recorded out of Bulawayo.

Gallo Records was looking for tunes for audiences who were tired of colonial (and now apartheid) prescriptions around ethnic and cultural identity. ‘Ag, why do you dish out that stuff man?” the incoming editor of Drum magazine recalled a man in the street saying to him in 1951: ‘Give us jazz and film stars, man! We want Duke Ellington, Satchmo, and hot dames! Yes, brother, anything American’.

‘Skokiaan’ was going to become American, very American: Satchmo was coming. But before that, before Louis Armstrong’s voice forever annexes Musarurwa’s wonderfully free lines on the sax, the original version is a local hit. A 1954 re-recording by the (now renamed) Bulawayo Sweet Rhythms Band sells 170 000 copies in southern Africa. Musarurwa described it as tsaba tsaba, a high-energy jive that sounds like New Orleans swing, vaudeville and jitterbug filtered through southern African jazz and vocal stylings, with some conga and rumba in there too. It was a Zimbabwean take on the marabi sound that came back with migrant workers returning from Johannesburg.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, a ‘trad boom’ led to a revival of 1920s American swing in post-war Britain – so-called ‘traditional’ jazz, which was largely the sound innovated and globalised by Armstrong. British trad jazzers were reconstructing early ragtime and the New Orleans sound. One cycle of 20th-century nostalgia had run its course, producing big bands and skiffle groups, with people playing washboards and (in a throwback to the Jazz Age) the C melody sax.

These records – nostalgic British reworkings of American ‘hot’ jazz – then travelled to Northern Rhodesia (now Tanzania) and Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) with the wave of white settlement that followed the Second World War: one more element in the transnational, transcultural saga that following a song like ‘Skokiaan’ takes you into. A Rhodesian ‘Police Band’ playing an anarchic, Afro-Dixie, colonial/carnival tune about a drink brewed against the law, sometimes drunk out of tea cups to fool the authorities: ‘Maize and sugar and a little meths. Strong and dangerous’. Moonshine in America, chikoliyana in Shona. In Zulu: skokiaan.

‘Everyone knows that’, says Musarurwa. But then reflects that perhaps the Americans didn’t quite get it, considering what boomeranged back when Gallo despatched the disc to UK Decca, who sent it on to their US subsidiary, London Records. ‘On the way the record broke but the American’s heard the tune through the crack’, read Musarurwa’s words: ‘Skokiaan was a hit’. The instrumental that he had crafted from two saxes, two banjos, traps and bass was immediately re-recorded (as hits by black artists generally were) for the ‘popular’ (i.e. white American) market.

‘Skokiaan’ was set to words by Tom Glazer, an American folk singer who had worked with Lomax at the Library of Congress (and would also transpose songs by Miriam Makeba and The Manhattan Brothers into English: ‘Kilimanjaro’, ‘Lovely Lies’). Glazer took the bouncy sax lines and made them into a horribly catchy ditty, one that charted in the US in three different versions, stayed there for eight weeks running and was covered at least 19 times within a year of its release. One version was by Louis Armstrong, whose famous, gravelly voice now closed a loop of African/American musical history:

Ooooh….Take a trip to Africa, any ship to Africa

Come on along and learn the lingo, beside a jungle bungalow…

If you go to Africa, happy, happy Africa,

You’ll linger longer like a king-oh, right in the jungle-ungleo.

Skokey-skokey, skokey-skokiaan

Okey dokey, anybody can

2.

Of the three channels – image, music, text – which make up Penny Siopis’s short films, the image and text tend to work in fairly constant ways, at least in terms of form and function. The visuals are culled from found footage: random 8mm or 16mm amateur spools that are sifted and arranged in a shifting collage according to intuition, happenstance and fascination. The text – resonant, revealing or cryptic phrases drawn from the artist’s research – ‘mimics the form but not the function of the subtitles we often find in foreign films’. It is not actually translating anything, in other words, but is experienced instead as a strangely intimate address, perhaps silently sounded out in the consciousness of the viewer.

But the third channel, audio, is perhaps more variable in the role that it plays, more flexible and harder to characterise. Sometimes, as in ‘My Lovely Day’, the sound is part of the archival grain, as when we hear a recording of the artist’s mother singing on a 78-rpm gramophone record. Sometimes, as in ‘The Master is Drowning’, the sound collage is made from fragments of Western classical music: piano sonatas and funereal marches, snatches of symphonies, fading in and out. With these the effect can be reminiscent (as the artist points out) of the music in early, ‘silent’ films of the 1920s and 30s: a means of emotional pacing, punctuation and emphasis.

By the mid-20th century, the Hollywood film soundtrack becomes the cultural terminus for large swathes of classical music (more accurately: German orchestral music of the Romantic era). Screen action or dialogue underscored by strings, piano, woodwinds and percussion: a globally shared and immediately legible means of coding emotional response, and of knowing what we are supposed to feel at any given moment. So when the music in Siopis’s films seems to be a soundtrack but isn’t really; when the emotional confirmation and guidance that comes built into the concept of the underscore is rendered fragmentary, discontinuous, stop-start or stuck in a loop – then it’s not quite so easy to work out what to feel, or what to do with the sentiment and nostalgia that has been automatically (perhaps fraudulently) released.

A large part of her sound world comes from Greek and Turkish folk music, particularly the mournful rembetika that emerged from the 1922 Turkish-Greek conflict, and the ‘exchange of populations’ that resulted (when ethnically Greek communities were expelled from homes in Asia Minor ‘to a Greece entirely foreign to them’). This is the prehistory that underlies the acerbic, subtitled words of Siopis’s grandmother in ‘My Lovely Day’, who is exasperated with the silly ‘escapades’ of her grandchildren as they fool around in the garden. The footage shows dress-up parties and synchronised swimming. Everyone kicks in a circle and the water churned up in the centre makes the screen burn white as if damaged or over-exposed.

In ‘Obscure White Messenger’, the string laments and hoarse chanting that accompany the words of Demetrios Tsafendas produce a strange, compelling mixture of sound and image. In one sense this rough-edged Turkish folk music seems discontinuous with the story that the viewer is trying to piece together: a South African story of the killing of apartheid Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd and the life of his assassin Tsafendas. The musical language is different to the conventional idiom of soundtracking or documentary: neither subtly insinuating string orchestras nor sentimental, nostalgia-suffused period pieces. The effect is bracing, liberating. Because the music is non-South African (and non-European?), you are not provided with recognisable cues and structures of feeling that would accompany, say, a background of 1950s Sophiatown jazz. Instead, the sound is fierce and strange, more like a mantra or a dirge than a narrative proposition. So the viewer is not offered the expected sonic handholds, and the intensity cannot easily be sublimated or translated into the correct emotional response.

This kind of disjunction works to create the dreamlike quality of the films – the word dreamlike is over-used, but I mean it as arising in a quite technical sense. It comes from the way that semi-random bits and pieces of found material (the film analogue of what Freud called the tagesreste: the ‘day’s residue’, the arbitrary bric-a-brac of everyday life) are shuffled and patterned into a puzzling, obscure new logic. And in a way similar to how the ‘dream-work’ runs its processes within the sleeping brain, using whatever clutter is to hand in the short-term memory. So the most ordinary scenes – life-saving practice, egg-and-spoon races, tourist footage of scenery, river cruises and carnivals – come to be imbued with a ‘psychical intensity’, a latent charge that cannot be explained by their surface or literal content. Then there is also the larger, political resonance that builds across the films: their evocation of colonialism and white rule in Africa as a kind of extended, waking dream. Such scenes were hardly ordinary in the first place, certainly not in a place like this.

In another sense, the music of ‘Obscure White Messenger’ does have a direct linkage to its words and images. This Mediterranean or Anatolian sound world resonates with the complex, wandering life of Tsafendas: a man of mixed Swazi and Cretan heritage who found solace in ports like Alexandria, Lisbon, Athens and Istanbul. And who (a recent biography of him reveals) loved folk music of deep historical struggle and resolve. His favourite song was a deep baritone version of ‘Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child’ by Paul Robeson, the African American leader, actor and trade unionist who would become a leading voice in the civil rights movement. Tsafendas also liked ‘Zot Nit Keymol’ (Song of the Warsaw Ghetto) which he would sing in Yiddish, having memorised the lyrics.

His favourite books included Emile Zola’s Germinal (about the exploitation of 19th-century coal miners) and Rabindranath Tagore’s The Home and the World (the story of a political awakening in colonial India). He also loved Brecht and Dostoevsky, and would quote a line from Demons when discussing his killing of Verwoerd, in his old age: ‘It’s easy to condemn the offender, the difficulty is to understand him’. He travelled with a battered suitcase containing the Freedom Charter, a poster honouring Patrice Lumumba as well as several Bibles (in case he needed to pretend that he was a missionary). His reading habits meant that he was nicknamed ‘the lending library’ as a boy in Lourenço Marques (now Maputo). And when reminded of this by a friend who caught up with him in Umtali (now Mutare) in 1964, Tsafendas went to his battered suitcase and gave her copy of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

The open form of Siopis’s films – their way of amplifying the strangeness of the past the more they are looked at, rather than reducing or rendering it too easily knowable, recognisable or usable – this openness means that her moving and endlessly watchable treatment of Tsafendas’s life is able to do it a kind of justice denied by more narrowly documentary treatments of his life. ‘Obscure White Messenger’ absorbs these newly uncovered facts about the life of its subject into a ramifying dream-work, without needing to make them merely data points in an argument over whether Tsafendas’s act was ‘political’ or not (and so draining them of their resonance, or the psychic energy they transmit across time).

The more we know about the past, these film-works seem to say, the less we can say about it with any certainty. And then through all their sepia tints, sprocket marks and liver spots of aged celluloid, the scenes of vanished people and places also silently broach another, more universal question: Do you think I was any less real than you?