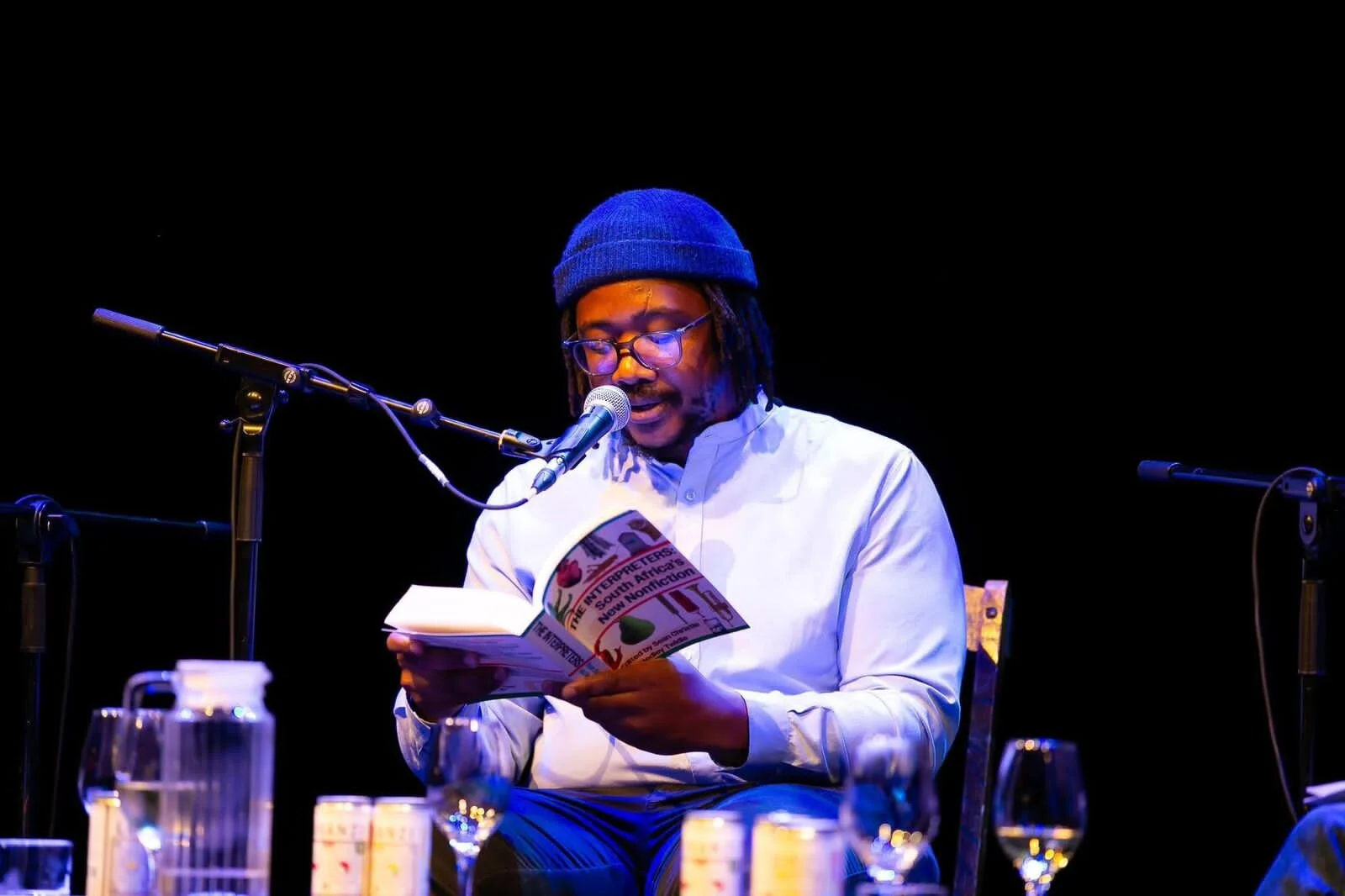

The Interpreters

A landmark anthology of literary nonfiction.

Across three decades of democracy, South Africa has seen an outpouring of longform, narrative journalism and creative nonfiction – genres in which some of the country’s finest writers have tried to make sense of a complex and changing society. This one-of-a-kind anthology collects the best literary nonfiction published since the end of apartheid. From the underworld of zama zama goldminers to the tragicomic closure of a Cape Town zoo, from stick fighting to punk rock, game lodges to fruit farms, cricket pitches to mermaids, The Interpreters: South Africa’s New Nonfiction assembles a range of true stories that are as compelling as any fiction. The editors have combed through 30 years of writing to produce a collection that combines preeminent names with lesser known but no less immersive and powerful works of narrative nonfiction – disparate views and voices that, when read together, have created a new topography of South Africa’s recent past.

Published by Soutie Press. Cover design by Gretchen van der Byl.

Insta: @soutiepress. Order here.

“This magnificent anthology will surely emerge as one of the best books out of South Africa this year, if not this decade.”

“This anthology honours a form of writing that has long lived on the periphery of South Africa’s publishing economy. The longform essay. The deeply reported fragment. The story that takes months, sometimes years, to unfold. It’s subtitled the “new non-fiction”, but really it feels like an ancient artefact, polished and restored to its former glory. [...] One of my first published essays was over 6,500 words; a piece on Cape Town’s then-emerging jazz scene, written for Chimurenga Chronic, back when it was still possible to explore a single story with the care, depth and temporal generosity it deserved. This kind of writing rarely makes commercial sense, but it’s where some of the most urgent, lyrical, and politically textured storytelling still lives.”

“A magnificent collection. The selection is superb; these are surely among the very best of this kind of reportage to be written in or about South Africa since whichever point in time designates the new.”

Introduction to the anthology. Johannesburg Review of Books, 14 August 2025.

Interpreting The Interpreters. Q&A with Lifestyling, 2 June 2025.

Five great reads from 30 years of real-life stories: a listicle in The Conversation, 12 June 2025.

A celebration of longform: Inside one of SA’s most remarkable anthologies. Q&A with Ferial Haffajee. Daily Maverick, 16 June 2025.

Interviews with Radio 702, FMR, SAFM and Cape Talk.

Launch at Love Books, Johannesburg. Sean in conversation with Anton Harber, Bongani Madondo and Zanele Mji.

Longform journalism is (almost) dead. Long live longform journalism. Sunday Times, 29 June 2025. Sean on the history of literary journalism in South Africa, page one and two.

“Q: Given that Hedley and you are friends, how did the book come to be, and how did you enjoy the process of working alongside one another?

A: It has quite a long history. We have been friends since schooldays, and corresponded about books throughout our university years, including an eclectic mix of nonfiction, and I mean super-eclectic: everything from Gaston Bachelard’s Poetics of Space to Deneys Reitz’s Commando. We were into the work of British psychogeographer Iain Sinclair, and his London Orbital, about walking London’s M25, inspired a very precocious decision to move to Cape Town to do something similar with the city’s main road, which runs from the Castle of Good Hope to Simon’s Town. We completely failed to write that book, but we both took the experience of trying to write it into other things: Hedley into his PhD thesis, and I continued to haunt the lower part of the city, and ultimately wrote a book about a community of maritime stowaways living under the foreshore flyovers (Under Nelson Mandela Boulevard). We never imagined we would try and do another book together, but once we started talking about this project it just flowed. Assembling The Interpreters did not feel like work at all, more like the intensification of a long-running conversation. A joy, to be honest.”

“Writing is the one art that compels the writer to explore and express complex feelings and thoughts through an attempt at simplicity and concreteness that are yet able to preserve the complexity.”

A cocktail of true and false. Financial Mail 15 May, 2025.

Kragtige boek, ’n amulet teen die vuur. Die Burger, 26 May 2025.

A powerhouse of new South African nonfiction. LitNet 3 June, 2025.

The Interpreters is outstanding. TimesLive 5 June, 2025.

Found in translation. Currency, 16 June 2025.

A bumper pack of multilayered and complex ‘slow journalism’. Business Day, 19 June 2025.

The Interpreters gives us a great deal of rich, factual storytelling. News24, 31 July 2025.

“At one point Madondo describes a visit to hospital, where Brenda is in ICU, and how their party becomes elated when Brenda moves her fingers, so much so that a security guard shushes them and says something like, ‘This is the ICU, the closest to where death and angels reside’. And Madondo writes ‘Wow! Security guards gripped by poetic seizures? Only Brenda could get that right.’ This truly opened my eyes to the possibilities of the form. I mean, I come from a Sunday school background and a society that’s quite regimented, where the idea is that if you play by the rules, you’re doing OK. And here was an African writer not playing by rules.”

“I wasn’t someone who knew what he wanted to do, but I remember reading that zoo piece and thinking oh shit, here’s a way of doing interesting stuff and meeting interesting people, in a country were so many of us just buzz around in the same limited social and cultural circuits. A vocation! Things were never really the same again.”

“[Sandile] Dikeni fantasised about starting a publication called Bongo, a nod to Drum, in which he would publish all kinds of shit, including the 15,000-word e-mails that Comandante Marcos was sending out from Zapatista territory in southern Mexico. Incredible, literary stuff, written from the ground, which absolutely nobody was putting in print,” said Edjabe, who attended the Grahamstown festival in the year 2000 with Dikeni, and sat there enchanted as Njabulo Ndebele talked for 90 minutes about Brenda Fassie. “I just knew I had to publish it somehow,” said Edjabe, who built Chimurenga Issue 1: Music is the Weapon (April 2002) around this Ndebele piece. For the next decade and some, Chimurenga created a space “for nonfiction that nobody else would publish.”

“I have always grappled with the fact that the truth cannot be packaged into one soul or one mind alone. It is something fragmented, there is so much to it, the truth is varied and scattered across the world. [...] So, what do I do? I gather together the feelings, ideas, words of everydayness. I put together the life of my times. I’m interested in the history of the soul, the being of the soul. All that the larger history usually misses out on, all that it is condescending towards. So I work on all the history that goes missing.”