Monsoon Raag

A journey in sound.

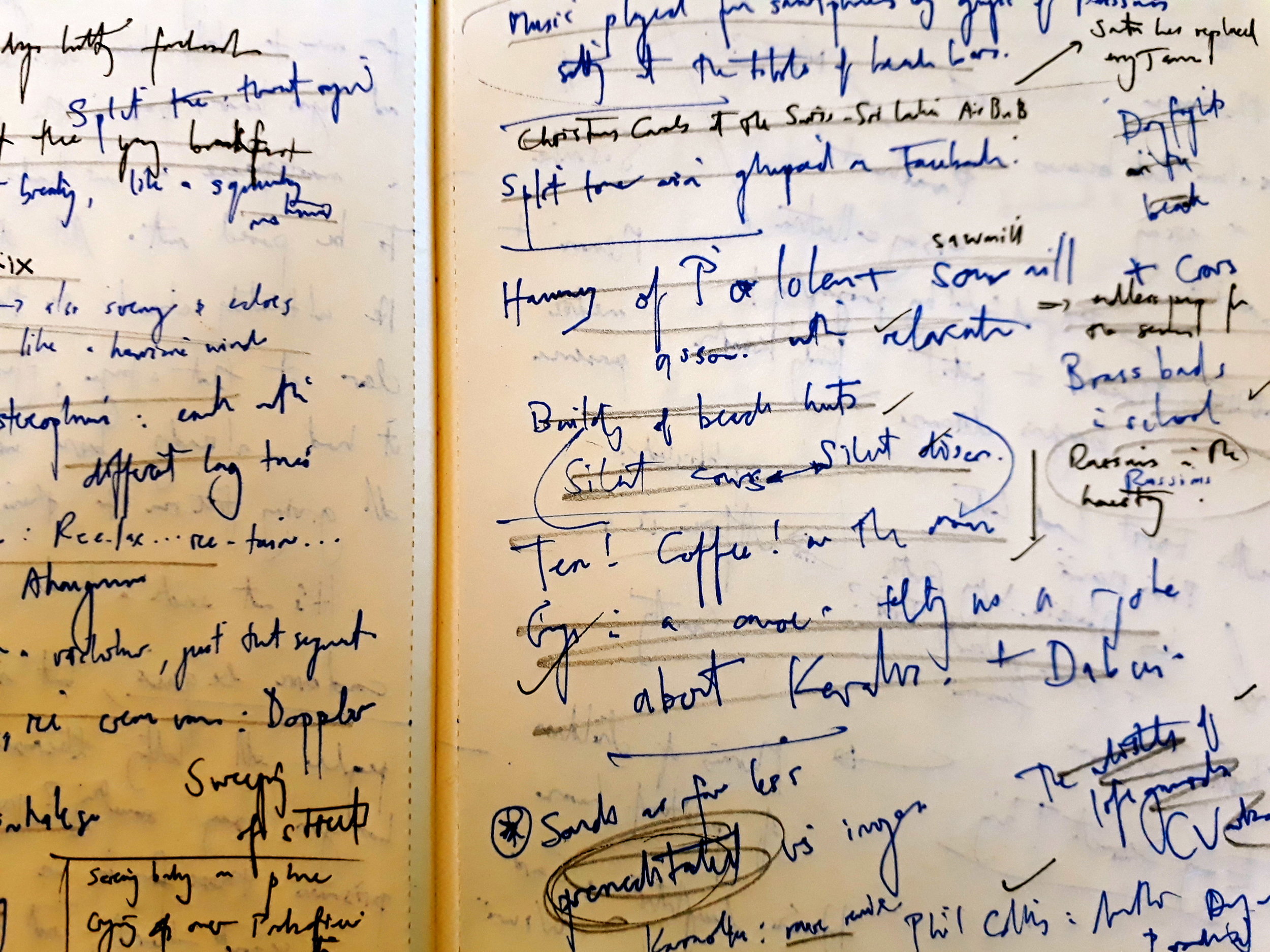

Prufrock, final edition, May 2019.

The days would begin with singing, but we never quite knew where it was coming from. Male voices in unison drifting into our room while it was still dark, at the edge of waking. Early morning singing or chanting in Fort Kochi, voices coming from…we could never tell exactly: maybe the Basilica, the rooftop mediation hall beyond the football pitch, the Young Men’s Buddhist Association over towards Mattancherry. Days were edged by this unison singing, in and out of sleep, the sound of people beginning the day together.

*

‘Join us for a morning raag’, said the man at the Kathakali Theater, bringing his palms together, bowing slightly, dropping his voice to whisper: ‘Most welcome’. He had one of those voices that tickles the eardrum, that creates ASMR-like shivers even at a distance, that you want never to stop. We would bow and intone it huskily to each other all through two months of travel in south India and Sri Lanka: ‘Most welcome’.

The idea is distinctive to Indian classical music – that certain scales and melodic sets are associated with certain times of day, or seasons of the year: the heat, the rains. But it seems (once you have heard it) utterly logical, beautiful, impossible to do without. A raag, or raga, is not quite a scale (because many ragas can be based on the same scale), and not really a tune (because the same raga can yield an infinite number of tunes.) It has no direct translation in Western music theory, but with it comes the idea that certain patterns of sound have specific effects on the mind and body, that they colour things, hence the Sanskrit origin of the word raag: concerned with pigments and tinting, tingeing or dyeing.

*

At night, the younger guy who takes over the reception desk at Raintree Lodge watches series or movies on his phone. The tinny noise keeps us a little awake, slows down our wifi connection to almost nothing. But he is such a friendly guy, all alone all night, so we never tell him to stop. Never get his name, but he has a topknot, so we call him Man Bun Man, which somehow gets put to the tune of The Beatles’ ‘Nowhere Man’: Man Bun Man…don’t worry…Take your time, don’t hurry…

In White Noise, Don Delillo gave us ‘The Most Photographed Barn in America’. Raintree Lodge must be the most photographed hotel in Kerala. All day there are shoots happening on its front doorstep, against the vines and creeper-covered balconies of the front façade. We suspect there is something we don’t know about: that is has been the location of a famous film or music video. Perhaps some undeleted images still exist of us walking through a door to join the happy couple or the fashion model, unintentional photo bombers. We even learn to the recognize the sound of a shoot from our upstairs room: the particular call and response of instruction, question, suggestion, preparation, action…

*

A particular grunt during a Kathakali performance. The scene is from the Mahabharata, in which the evil, red-and-green faced Kichaka is trying to seduce the beautiful Malini as she serves wine, lunging at her like a heavily made up Harvey Weinstein. The words are being sung by someone else (Most Welcome), but every now and then the lascivious Kichaka, eyes reddened by seedpods, lets out a commanding, guttural, coughing grunt as he points to his bedchamber: Hah! It is a shockingly ugly sound, condensing millennia of sexual harassment into a single vocable.

*

‘Nowhere Man’ is a song I just woke up singing one day. Anna keeps a record of these, what she calls my ‘morning jukebox’, trying to discern what it might be revealing about my subconscious life. It’s very random though: now Ronan Keating (‘Life is a Rollercoaster’) now R. Kelly. One day it’s a song that a fellow protester tried to teach us as we advanced politely on parliament: uZumahhh! uGuptahhh! Then a question along the lines of: where is all the money you ate? One morning the magnificent, man-confident first line of a Fleet Foxes song that I haven’t thought about for years just comes rushing clean out in the shower – So now that I’m older /than my mother and father – and knocks around in my head all day, not making much sense, until the rest of the verse is dislodged from memory: when they had their daughter / Now what does that say about me?

Seeing Rabindranath Tagore on the shelves of Idiom Books sets off an overnight chain of association which draws up an obscure EP by Bonnie Prince Billy, ‘Get on Jolly’, his slow, wonky setting of the love poems from Gitanjali, full of drones and warbles and guitars fed quietly through a reverse pedal:

When you ask me to sing

I feel like my heart would burst with pride

And I look at your face

And tears come to my eyes

All that is harsh and wrong melts into one sweet song

And my loves spreads wings

Like a glad bird flying over the road

I am here to sing you songs

In your room I have a corner seat

In your world I have no work to do

My useless life can only break out

In songs that have no purpose

*

Travel means relinquishing control of what music is playing around you. In the cafes you hear an unpredictable cross-section through globalised pop culture. Who would have thought that Phil Collins would be so popular in the tourist resorts of Kerala? ‘Another Day in Paradise’ comes around often, even in a chunky house remix. Ed Sheeran’s ‘Shape of You’ is everywhere; it has also been given the bhangra treatment. It’s like the masala Coke that Suketu Mehta writes about in Maximum City: the same fizzy black liquid, but with lemon, rock salt, pepper and cumin added. The couple of teaspoons of masala in the glass attack from the bottom, ‘the American drink froths up in astonished anger…And, lo! It has become a Hindu Coke.’

One day we wait for the slowest veg burger ever made and are astounded by the length of Jack Johnson’s back catalogue. He goes on with his gentle post-surf strumming and crooning for hours. WHY don’t the NEWS readers CRY when they TALK about PEople who DIED? Oh I was hungry and those kitsch, emotionally fraudulent triplets were driving me mad. COUldn’t they BE decent EEnough to HAVE just a TEAR in their EYE?

In an art gallery I suddenly snap into awareness of Bob Dylan singing a line of the charity song ‘We Are the World’: It’s TRUE we make a better DAY just YOU and ME! Can it be true? This pained, nasal, ridiculous rendition leads me to find footage of him rehearsing the song, continually getting it wrong (‘Just play it again Stevie?’) holding up the lyrics sheet, looking around, bewildered at how they had all found themselves in the middle of something so well-meaning and so inane.

*

Brass band music from the primary school next to the café where I am working. Boisterous music-making, with lots of cymbal clashing and squawking and showing off. The trumpets and trombones and tubas carry that tongue in cheek, over-the-top, magnificently childish and comic sound that brass instruments can have – a truly joyful noise. Bits of school assembly drift out through the grilles and brickwork, becoming part of the soundscape of a town. Children practise their English in emphatic call and response, or recite the national pledge with gusto:

India is my country and all Indians are my brothers and sisters.

I love my country and I am proud of its rich and varied heritage.

I shall always strive to be worthy of it.

I shall give my parents, teachers and all elders respect and treat everyone with courtesy.

To my country and my people, I pledge my devotion.

In their well-being and prosperity alone, lies my happiness.

*

Even before the early morning chanting: the sound of streets being swept (and swept and swept and swept).

*

A yoga lesson under a tin roof at the top of a building, a late addition to the monsoon falling. Being amid, watching, hearing heavy rain is one of the great highlights of this journey, after the long drought in Cape Town. Hitting the world in their millions, the droplets activate other dimensions, change your perception of space, colour and smell. In child’s pose, in corpse pose, I lay there listening to it fall on the bus stop and the Reading Rooms, the roof and the pavements, each contributing their distinctive note.

I thought back to a documentary, Notes on Blindness, that I had seen a couple of years ago. The audio track of the film was a taped diary recorded in the 1980s by a man named John Hull, an Australian theologian and academic who chronicled the experience of losing his sight. This audio diary was then worked into a film and sometimes ‘performed’ (i.e. perfectly lip synced) by the actors playing him, his wife, his family. The most beautiful passage describes him preparing to leave the house one evening, then opening the front door to find rain falling:

I stood for a few minutes, lost in the beauty of it. Rain has a way of bringing out the contours of everything; it throws a coloured blanket over previously invisible things; instead of an intermittent and thus fragmented world, the steadily falling rain creates continuity of acoustic experience.

He goes on to give a the most beautifully intricate description of this soundscape, remarking that while he knows the local phenomena of shrubs, footpath, front gate, culvert to be there in theory, normally they give no immediate evidence of their presence: ‘I know them in the form of prediction. They will be what I will be experiencing in the next few seconds.’ By contrast, the steady rain, transmitting its acoustic data, ‘presents the fullness of an entire situation all at once, not merely remembered, not in anticipation, but actually and now.’ At this point the film shows droplets cascading down over study desk, sofa, dining room table, a domestic monsoon:

If only rain could fall inside a room, it would help me to understand where things are in that room, to give a sense of being in the room, instead of just sitting on a chair.

This is an experience of great beauty. I feel as if the world, which is veiled until I touch it, has suddenly disclosed itself to me. I feel that the rain is gracious, that it has granted a gift to me, the gift of the world. I am no longer isolated, preoccupied with my thoughts, concentrating upon what I must do next. Instead of having to worry about where my body will be and what it will meet, I am presented with a totality, a world which speaks to me.

Have I grasped why it is so beautiful? When what there is to know is in itself varied, intricate and harmonious, then the knowledge of that reality shares the same characteristics. I am filled internally with a sense of variety, intricacy and harmony. The knowledge itself is beautiful, because the knowledge creates in me a mirror of what there is to know. As I listen to the rain, I am the image of the rain, and I am one with it.

*

But what I really wanted to record from the yoga lesson was the shocked, under-his-breath expression of our teacher – Oh-my-God! – as he let go of my legs and my attempt at a headstand crumpled towards the floor in a second. The exact same thing happened to Anna just after, to be met by an identical Oh-my-God! It was so different to the relaxed commands that he had been issuing in a hypnotic, nasal voice, Ree-lax, Ree-tain, a voice that steadily and strangely bent up through different pitches, like a filling bottle of water, as he counted out the holding of breath…One asana two asana three…

*

In south Goa: hammering. Wooden beach huts are being constructed ahead of the peak season. In Palolem there was also a small sawmill near our guesthouse. The hammering and sawing was so ubiquitous along the coast that eventually we acclimatized, and reading on a beach seemed incomplete without a friendly thudding in the background.

*

Tea! Coffee!

Anyone who travels in these parts will hear the calls of chai sellers on street corners, on railway platforms, in carriages. It is the audio equivalent of a sunset picture at the Chinese fishing nets, or being snapped on that bench in front of the Taj Mahal, a spot where the fabric of the visible world has been worn so thin, like a map where people have pointed out, in the sense of rubbed out, the You Are Here.

But now we are kayaking around a small islet in the late afternoon, and we bump into two young guys who are flailing their paddles around and laughing about how bad they are. They say they are from Kerala but working in Dubai, and when we remark that we have met many Keralans who work in Dubai they say oh yes, have you heard the one about when the moon guy got to the moon and said ‘One small step for man…’ and then a voice piped up ‘Tea! Coffee!’ And then they laughed hugely and kept failing to pilot their boat round the islet. ‘Us Keralans get everywhere you see…’

*

There are many Russian tourists in Goa (there is a direct flight from Moscow). We joked about taking our place as a minor partner in the BRICS alliance: Brits, Russians, Israelis, Czechs (or Croatians or Chechnyans), South Africans. Travel, for some members of the alliance, did not mean relinquishing control of the music around them. Often, a group of Russians would set up a smartphone on the table of a beach bar and begin playing their own music – tinny EDM or house beats, like a radio transmitter picking up frequencies from the motherland.

*

Silent cows. Silent disco. After the millennium, legislation was passed to curb the infamous trance parties that had taken hold on Goa’s beaches since the 1970s. There have been several ‘rave crackdowns’ since. Now you see the revellers behind the boulders at the end of the beach, headphones on, strutting, marching, two-stepping, alone together. The shared enthusiasm for psytrance in Israel and white South Africa – something to be investigated. A garish culture grown out of a kit on barren soil, a homeless sound, a nowhere music.

I go back to Mr Fernandes’ Homestay and show Anna that immortal meme of ravers set to the Benny Hill theme tune.

*

To get away from the sawmill, we moved into a tree house in a jungle. Each night we heard the plastic bag in the bin rustling, but ok: it was an open tree house and other organisms were coming and going. On the fifth night, I realized that there was no plastic packet in the bin. It was my packet of dirty laundry rustling, or being rustled. I switched on the light to see an unusually large mouse headed across the floor.

‘There are two of them, no it’s pregnant, no it’s a rat, no – it’s got your sock!’

It was carrying off the second of my (favourite) green socks. At this point, Anna laughed for a long time, reflecting on what a long-term project this had been, almost a civil engineering project, night after night. In the morning I found boxers scattered through the foliage below the tree house. The green socks were never recovered.

*

An over-revving scooter that has fallen on top of my leg on a gravel track in the hills above Agonda. Over the course of two weeks, my foot, leg and buttocks develop a slow-building archipelago of bruises in a bizarre, hard-to-understand pattern, as if they are revealing something secret about the underlying musculature or skeleton. Such a minor fall, such an angry rev, such an expressionist array of bruises. I take it as a warning and keep to the tarred roads, much more slowly.

*

Crows and dogs. Crow fights and dog fights. On the beaches, in the alleys, from neighbouring villages at night. When we live in the tree house, there are other bird sounds. Anywhere else it is the soundtrack of the Anthropocene, the ‘Despacito’ or Ed Sheeran of the bird-singer-songwriter world, our shadow species: crows.

*

Hooting and your changed relation to it – learning not to take it personally. How many shades of meaning can be compressed into a single sonic gesture, a single automotive squawk. Watch yourself, excuse me, here I am, coming through, seen you, thank you, on your way, no worries.

*

Moving from south India to south Sri Lanka, song-like Malayalam (just a beautiful word to say) turns to the more staccato, percussive Sinhalese: to the outsider, some conversations can sound like a drum solo, free jazz.

*

On the train journey down the coast from Colombo, the gangway between the two carriages is clanking as we go over bumps. It is an extraordinarily loud and unpleasant sound. All the casually violent noise we absorb: what does it do to us? I once met a sound artist who had made detailed, granular recordings of Manhattan traffic. All the carnage that was to come, he said – 9/11, Iraq, mass shootings – could be heard in that sound. It was all present, latent, nascent, if you just listened, really listened, to that rush hour intersection.

A commuter from Hikkaduwa tells me about when the tsunami hit the Matara Express just around here at 9:30 am on Boxing Day 2004. Eight other trains on the line were held back, but one could not be reached by the signal operators, and kept advancing towards the wave. It was the worst rail disaster in history: over 1700 lives lost. Two carriages survived in working order and are still used on the line, marked with a painted wave.

On my Kindle, I had been reading an extract from a book about the Japanese tsunami of 2011, about how coastal communities rebuilt and reckoned with what had happened. A survivor remembered:

It was a huge black mountain of water, which came on all at once and destroyed the houses. It was like a solid thing. And there was this strange sound, difficult to describe. It wasn’t like the sound of the sea. It was more like the roaring of the earth, mixed with a kind of crumpling, groaning noise, which was the houses breaking up.

The line from Colombo to Galle was repaired and runs close along the ocean. Between the hotels, fishing boat harbours, beach shacks, petrol pumps and Buddhas, you see small cemeteries in the grass, under the coconut palms, small memorials, up-turned stones, faded murals.

The two overlapping gangways keep clanging – an unbearable, unbelievably violent sound. I wonder if it’s just me, but then a fellow tourist gets up and begins filming the phenomenon. It stops as soon as he points the iPhone at it.

‘Stay there,’ his friend says, ‘Stay there and keep it quiet’.

*

Sitting outside our room on the shared balcony at the guesthouse, I think I heard the couple next door having sex. They came past, said hi, went into the room and then it began. It made me into the sonic equivalent of a voyeur, an écouteur (though that also means earphone in French). They were young but it sounded like good, mature, relaxed sex. Lots of talking and laughing, unhurried, and then the occasional sharp intake of breath. It could have been something else – one dabbing a cut on the other’s body with Dettol, or clipping toenails, anything intimate and attentive.

*

Walking along the walls of the Dutch Fort in Galle when the call to prayer sounds out from the mosque that is draped in fairy lights. The man has skills. On the third Allah hu akbar, he slides up to a keening, perilous high note right at the limit of his head voice, skirls around in this ecstatic zone, loops and glissandos down again.

The sun was calling it a day out there, beyond the petrochemical fug that slides over the Indian ocean from the subcontinent. The event was being solemnly saluted from the ramparts by hundreds of outstretched arms and tripods, raised phones and selfie-sticks. This sunset of 17 November 2017, a pretty average one, was probably generating more data than the whole of human history had up until the 1970s. Two billion digital images are uploaded every day. Each sunset adds terabytes more data; each one, refracted via the vast compound eye of the human race, must be stored in some air-conditioned server somewhere, digitally warehoused in Oregon or South Korea or Bengaluru.

Thousands of pics slide across our eyeballs each day, most given no more than a microsecond, no real purchase. Doctored and cosseted by those putting them up; consumed, swiped over in an instant.

I thought that collecting sounds instead of sights might offer something less…premeditated. Roads and train lines and the walls of coastal forts convene the world quite strictly, usher us towards particular places to stand and look, point and shoot. Sounds cut across space and cut in at inopportune moments. They cannot, by definition, be picturesque? They might often be meaningless, or less easy to cram with easy meanings: songs that have no purpose. It’s easy to look the other way; it’s less easy to block out a sound, which can be maddening, inescapable, unbearable. They go on happening in the dark.

The next day I realise that this call to prayer must be a recording, downloaded from elsewhere, Karachi or Qatar. The notes loop and curl in exactly the same way each sunset.

*

One afternoon there are thunderstorms in three directions – inland behind Galle, over to the east above the Peace Pagoda, bearing down on us from Hikkaduwa – each with different lag times. As people who grew up in a place of lavish electrical storms, Johannesburg, and now live in a place where you get maybe one a year, Cape Town, the sound of thunder rolling languorously around the horizon, taking so long to subside, for us it is like a tapping on a membrane of the subconscious, sounding out something half-heard, half-remembered, a noise field of intense, boundless, amorphous significance.

We watch and listen from the ramparts, hearing the shush of the fresh water meeting the salty sea just before it hits us. The sea is warm, so is the rain. The thunder has moved on, a few seconds elapsing after the flash. We float in the water off the walls of the Fort. The rustling of the seabed, the droplets striking your face and forehead – both are louder than usual, the water tapping on bone.

Listening to rain approach, set in, ease off, recede – day after day.

*

One of the young women who cleans rooms and prepares breakfast at the guesthouse has an unfortunate voice, one of those voices that sounds cracked or half-broken: half-young girl, half-old woman, not quite having coalesced into young adult.

These tiny young women are ordered around by a larger, older woman, Mrs Wickramasinghe, who sits on a sofa downstairs, directing operations from an iPad. She is sharp with her staff, matriarchal, but laissez faire with us.

‘After,’ she says when I offer to bring our passports, or pay for the month so far, ‘After, after…’

She is surrounded by several Dell computer screens that are divided into multiple CCTV feeds. One is of the kitchen upstairs, and so she might have seen me talking to the fish. A big pale fish with bulbous forehead, botoxed lips and a pained, humanoid face, suspended in a tank that seems too small for it.

‘I think the tank is too small for it’, says Mr Wickramasinghe, a lawyer, as he cleans the filter for the fourth time, ‘But it’s my son’s fish, and he wants me to keep it.’

His son is studying medicine in Belarus; his daughter is studying business management in Australia, and coming back home tomorrow for a holiday.

We look at the fish again when its caretaker has gone, and it looks back at us with wide eyes. Suddenly its whole body is convulsed with emotion, or agitation, or some kind of communicative passion – it is unmistakeably trying to tell us something.

As we are crouching there at eye level, it opens its mouth wide and lets out a long, soundless scream.

*

Something, we never quite work out what, plays out a wheedling version of Beethoven’s ‘Für Elise’, early in the mornings and late at night. It has that sound of the ice cream van: bending, wonky, Doppler-affected notes. Alarm clock, elaborate rickshaw hooter, doorbell? It remains a mystery.

There are very elaborate hooters in south Sri Lanka: multi-part klaxons on buses where the driver can obviously choose to go for the simple, the super, the super-duper, and then finally a button that activates something like a baroque chorale. The timbre evokes a quaint and archaic moment in the evolution of smart phones, the ‘polyphonic ring tone’, back in the day when mobiles still rang.

*

One of the most intriguing and ambiguous sounds of the trip is that made by local surfers as they paddle out among the beginners. It’s a bit like an owl hoot, a bit like a whistle, but hard to attach a definite meaning to. It’s not the internationally recognizable hoot of ‘Get off my wave’ since they do it when they are just waiting; it doesn’t seem to mean ‘Set coming’ either since the noise and swell don’t correlate. Finally, it just seems to say: ‘Here I am’, a gentle assertion of localism without wanting to put off the tourists, a warm-water warning.

The whole of southwest Sri Lanka is given over to surf tourism: red-nosed Russians and serious Japanese and stubbled Brits all paddling out, missing waves, falling off, while the locals will come charging and twirling through. Because this is very much a coastline for beginners and intermediates, there is a particular quality of intentness and striving in the water – among the non-locals, I mean. Those in the water are set on improving skills but also on the more complex social process of becoming surfers. They are wanting to shuck off their beginner-hood in this faraway location (a bit like those travelling abroad for a face lift) then return home triumphant and miraculously changed. So they are concentrating, maximizing. The locals banter away, the women on surf packages also seem to be having fun, but the visiting men don’t talk much. This is serious, and the seriousness is not to be punctured.

*

Anna has not gone back into the kitchen since the fish screamed. She has also asked me to cover the cooked, milky eyes of the red snapper that I have been eating down the road. The music in the restaurant (ABBA) is painfully loud and we debate for half an hour in whispers whether to ask the waiter to turn it down. Just as I have plucked up the courage, the French couple in front asks for the very same thing.

Anna and I high-five each other, having gotten what we wanted without asking. Such are the micro-dramas and micro-victories of travel.

*

The clunking sound of a gear change on an auto-rickshaw: ker-chunk. When travelling in south Asia you will soon discover if you are a Royal Enfield man or a scooter man. Or a tuk-tuk man. Mrs Wickramasinghe has organized one for me to hire, a caramel-coloured beauty, saying that it’s better for the sun. So we head off on the coastal roads accompanied not by the manly, Guevaran chug of an Enfield or the even-handed moan of a scooter, but by the two stroke tuk-tuk of the tuk-tuk and its chunking gears. I give it up after a few days though, since they are dull to drive and I have scraped the caramel on an electricity pole.

*

The silence of the back line.

There are all kinds of surf points along the coast – lazy lefts, rights, reefs, A-frames – but eventually I settled for mushy shorebreak off a shanty town at the edge of Galle, overlooked by a clifftop hotel on one end and a giant Buddha on the other, where a green jungly peninsula closes the bay. The water is blue-brown or pewter-coloured after all the rain. Occasionally it matches the quicksilver greys of the sky exactly and your eyes can’t pick apart the swells from the horizon – an eerie, beautiful effect, particularly as the light fades.

I get there on a bicycle or a tuk-tuk, and the men who run the surf shack (and, I suspect, sell MDMA to the Russians) usher me to the change room, pick out a rash vest and put an 8.6 longboard into my arms, something that is virtually impossible to miss a wave with. I try to get paddling immediately, since otherwise your feet brush strange things: the soft, feathery touch down there is most likely a plastic packet rather than a delicate seaweed. Sometimes there’s a sandal floating around, or an animal bone. The smoke of litter and leaf fires rises from the shore when you look back at the city. On the balcony of the hotel, flashes go off in the dusk but it’s not for you: more wedding shots in progress.

The swells are medium-small, slow, sometimes with long gaps between them. We bob out there in silence, full-grown adults, surfing in this shanty beach break, this scruffy urban shore.

‘So this is how it is?’ says Anna on the day she comes to bob around with me, ‘Kind of friendless?’

Entirely friendless: good training for advanced adulthood. The mysterious hooting of the locals continues, and today it seems more menacing. I am here and you should think about being over there, amid the kooks with the foam boards and coaches and whistles at the small end of the bay.

One afternoon a strong but skinny guy paddles right across me to poach a wave. On the one hand, it’s a total breach of surf etiquette; on the other hand, he’s a local, and maybe I should yield. But something stubborn made me not, and we got tangled up, him being yanked off the wave as my longboard snared his leash.

‘You trying to fuck me bro?’ he asked several times, ‘Are you trying to fuck me?’

I had to admit that, as a comeback, it was pretty much perfect. We sat tensely next to each other as the surf got flatter, until eventually I paddled over to the real beginner side, poaching waves from them in turn.

The light faded and first I thought it was the used-up thunderclouds blocking the sun, but in fact the day really was ending, the water becoming like liquid mercury and everything losing its 3D depth of field. The call from the mosque at Deweta slid across the bay, between the hotel and the Buddha, and I caught a last wave in and said goodbye to this odd pocket of water and time.

*

Time and the journey are running out. We are in a train back from Kandy to Colombo, a high line though tea plantations and hill fortresses. It goes through many tunnels, and as soon as it does, diesel fumes fill our carriage. No view, no beach, no surf break without its petrochemical underpinning wafting into your face: the trip has been a fossil fuel education, a doctorate in diesel. After a while some kids in another carriage begin screaming in the tunnels, playing with the echo. It creates an effect that is not easy to reproduce on a page of two dimensions. And that’s what these sounds, these memories of sound, are often doing: trying to create secret burrows and geometries behind the page, tapping the wall for hollows and backstories, probing the world with sonar like the bats hanging upside down all through the Botanical Gardens at Peradeniya, where we wiled away our last full day in Sri Lanka, feeling done with it all and a little homesick now.

*

Time is running out and an auto is taking us to an airport hotel. It speeds past a Pure Veg restaurant just in time for us to hear the string stab that comes after the verse in Billie Jean, just that perfect slice of pop and no more.

Hotel Paradise, is not, we decide, really an airport hotel. It has mauve mosquito nets and a porno bathtub with signs asking guests not to stain it with hair dye. It is a place for furtive sex by the hour and adulterous assignations in the no-man’s land on the far side of the runways, far away from the real airport hotels. It is permeated with a strong, musky fragrance. It is flown over by five aircraft in the course of the night, droning upwards or downwards, dragging their counterpane of sound over our horizontal bodies.

*

The screaming in the train tunnels had already set me on edge. It was done in jest but sounded like a hurricane wind, tearing down the world. In Trivandrum airport there was a man brushing his teeth after landing. Good practice – but he was making himself retch and gag. We all do this sometimes, I guess, trying to get to the back of the tongue. But he was doing it with furious intent, like penance, or as if he was addicted to the gag reflex, retching and choking himself right there in the middle of the bathroom at baggage reclaim.

*

On the flight to Dubai there is a baby crying. There is often a baby crying on flights; their ears take in so much more sound than those of an adult. They are rightfully terrified by the roaring and rushing, the painful changes in air pressure. They realise that they are in hell. But this infant screamed like no other I have ever heard. He screamed himself into exhaustion, into hoarseness, into a state of bewilderment and tiredness where the end of each wail seemed to lose its way and wonder what it was doing, and where it had come from, but then it was time for the next building wave of pain and panic, crashing against our ear drums and the moulded plastic of the cabin. My Kindle was stocked up with stories about the Trump administration’s tax bills, sexual predators, paedophile Congressmen, Sri Lankan cricketers choking and vomiting in Delhi smog, children who couldn’t go out and play six days out of seven, the selling of men into slavery in Libya, the wildfires engulfing California, the energy demands of Bitcoin, the genocidal Buddhists of Myanmar, the legacy of Robert Gabriel Mugabe, the threats of Hindu nationalists to behead Bollywood actors, the normalization of American Nazis, the sixth extinction, the dying corals and ceremonies of mourning held for vanished species – and I realized that this child was screaming on our behalf. Crying for all the newsreaders who never cried, for the fish who couldn’t scream, letting out a kind of primeval, end times, furiously sorrowful and exhausted roar that we crave, that would do us a lot of good, a kind of sonic retching to expel some of the poison, a flight-time wail of superhuman strength and endurance, out-screaming the engines in the cold dark air.

*

I was being poisoned by the in-flight meal but I didn’t know that yet, so I clicked through the entertainment channels. There was an episode of the cult animated show Rick and Morty where Earth is menaced by huge alien heads who hover in orbit and intone: ‘SHOW ME WHAT YOU GOT!’ The Pentagon is beaming them string theory and Da Vinci’s drawings but Rick tells the President that what they are actually asking for is music. Planet Earth wins out in a kind of intergalactic Idols (the other planets/contestants are all destroyed by a death ray) with Rick, Morty and Ice-T working together to create some jams. I watched it twice in a row – partly because I liked Rick’s song ‘Get Shwifty’ which saved Earth from annihilation, but also because the episode seemed to access some deep truth: that the only thing a superior form of extra-terrestrial life might ask of us would be music. That we might be in the beginning of the end for democracy, climate stability and possibly the human race, but didn’t we make some astonishing sounds in the one second of evolutionary time allotted to us.

Afterwards I found a documentary on the Estonian conductor Paavo Järvi – nothing special as a documentary but by the end I found my throat closing up over Sibelius and Scandinavian folk music. 36 million people are studying classical piano in China, we learned, and then saw footage of the young, punkish guy who had been placed top in the country, smashing his way through Prokofiev, unleashing torrents of musical energy. Then it was the finale from the The Firebird with its suspended, shimmering, otherworldly chords and (you know how it is on planes: the thin air, the wine, the compulsory reflection) I was crying into my refresher towel, thinking of humankind and all the gorgeous noise we made, once upon a time, at the end of the day.

October-November-December 2017