On Albert Camus’s The Plague: Part One.

Summer School, University of Cape Town, 2021.

Condensed version in English Studies in Africa 64:1-2 (2021).

Podcast with Bongani Kona, The Empty Chair, for SA PEN.

She taught me to read the book in a certain way, tilting it sideways as though to make invisible details fall out. — Kamel Daoud, The Meursault Investigation.

for D.B. (1981-2020)

1.

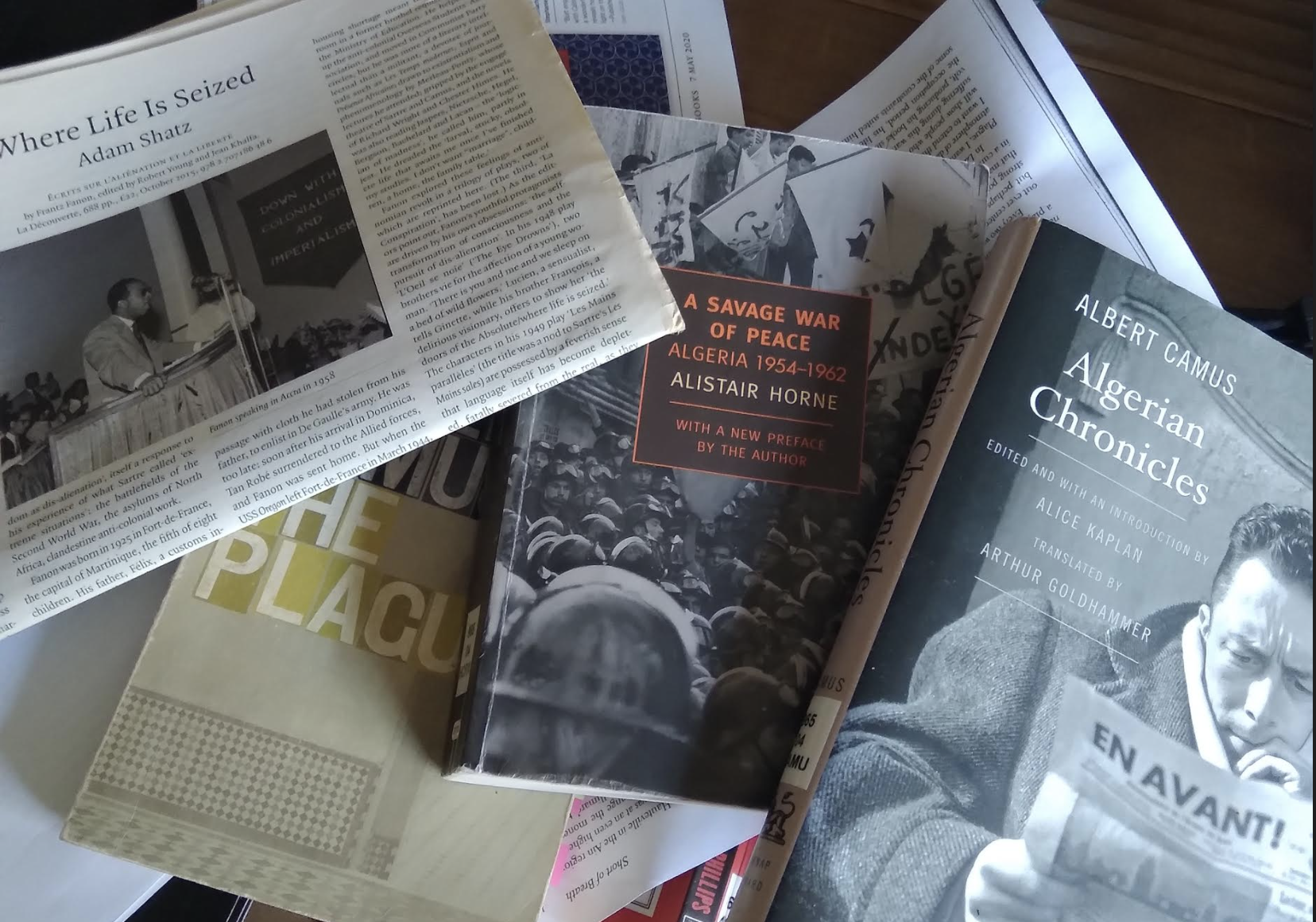

In 1947, Albert Camus published La peste, the story of a town struck by bubonic plague. He judged the book a failure, but The Plague is probably his most successful and widely-read work.

In one sense it is a simple story. Rats come out of cellars and sewers, spitting blood, and begin to die in the streets. Then people begin to die. The town is sealed off and we follow the experiences of a small band of characters as they battle the epidemic. Like a classical tragedy, the book is divided into five acts. In parts one and two, the death toll is rising; in part three it is at its height: ‘the plague had covered everything’. In parts four and five, the disease slowly retreats, and the town is liberated again. Amid the celebrations, the narrator strikes a note of foreboding, and the famous ending reads as follows:

Car il savait ce que cette foule en joie ignorait, et qu’on peut lire dans les livres, que le bacilli de la peste ne meurt ni ne disparaît jamais, qu’il peut rester pendant des dizaines d’années endormi dans les meubles et le linge, qu’il attend patiement dans les chambres, les caves, les malles, les mouchoirs et les paperasses, et que, peut-être, le jour viendrait où, pour le malheur et l’enseignement des homes, la peste réveillerait ses rats et les enverrait mourir dans une cité heureuse.

Indeed, as he listened to the cries of joy that rose above the town, Rieux recalled that this joy was always under threat. He knew that this happy crowd was unaware of something that one can read in books, which is that the plague bacillus never dies or vanishes entirely; it can remain dormant for dozens of years in furniture or clothing; it waits patiently in bedrooms, cellars, trunks, handkerchiefs and old papers, and perhaps the day will come when, for the instruction or misfortune of mankind, the plague will rouse its rats and send them to die in some well-contented city. (237-38)

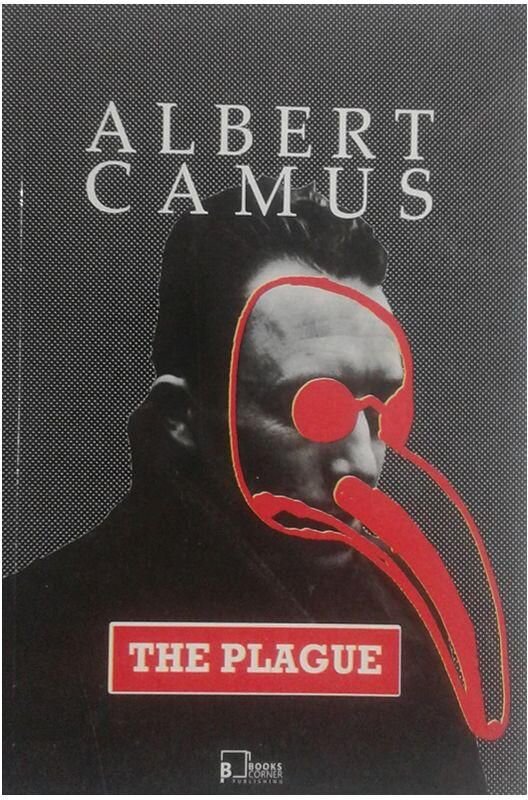

If you type ‘camus the plague’ into an image search, the huge archive of different book covers gives an idea of how many times this 20th-century classic has been read, translated, reprinted and repackaged. The more literal approaches go for rats and scythes; the more abstract show empty seascapes or dotted geometric patterns that could be microbes or epidemiologists’ models.

There is the photogenic Camus himself, in a famous Henri Cartier-Bresson portrait with cigarette and turned up collar. On one cover he has the eerie, beak-shaped mask of the Plague Doctor graffitied over his face. Used by physicians in Italian cities where the mortality rates reached up to 60% (in 1656, some 150 000 died in Naples alone), these 17th-century respirators had glass discs in front of the eyes and two openings just below each nostril. The ‘beak’ was filled with dried flowers like roses and carnations, herbs like mint, spices, camphor, juniper and ambergris, laudanum, myrrh, straw, perhaps a sponge of vinegar – anything to ward of the ‘miasma’ or bad air (Italian: mal aria) that was thought to spread contagion prior to the germ theory of modern medicine. ‘The inhabitants accused the wind of carrying the seeds of infection’ (130), we hear at one point in The Plague, a residue of the superstition that warm southerlies like the sirocco wafted plague particles across the Mediterranean from the deserts of Egypt.

The edition I have in front of me (second from right, bottom row) cost Rs 399 in Kerala, south India, from a bookshop in Fort Kochi that also seemed to function as a kind of shrine to Camus. Its bookmarks carry a quote from his notebooks on the back – ‘I know only one duty, and that is to love’ – and the owner told me that in this Communist Party-run state, The Plague had been on the school syllabus for as long as he could remember. This mass-market paperback edition has some violent brushwork on the cover, but leaves out the epigraph by Daniel Defoe, which is from the preface to the third volume of Robinson Crusoe:

It is as reasonable to represent one kind of

imprisonment by another, as it is to represent

anything that really exists by that which exists not.

What does this mean exactly? Is it reasonable, or not? I’ve never been quite able to work out how the epigraph should be applied to the novel. But the whole question of metaphor – of representing one kind of thing in terms of another – lies at the heart of the book’s enduring power, and of its problems.

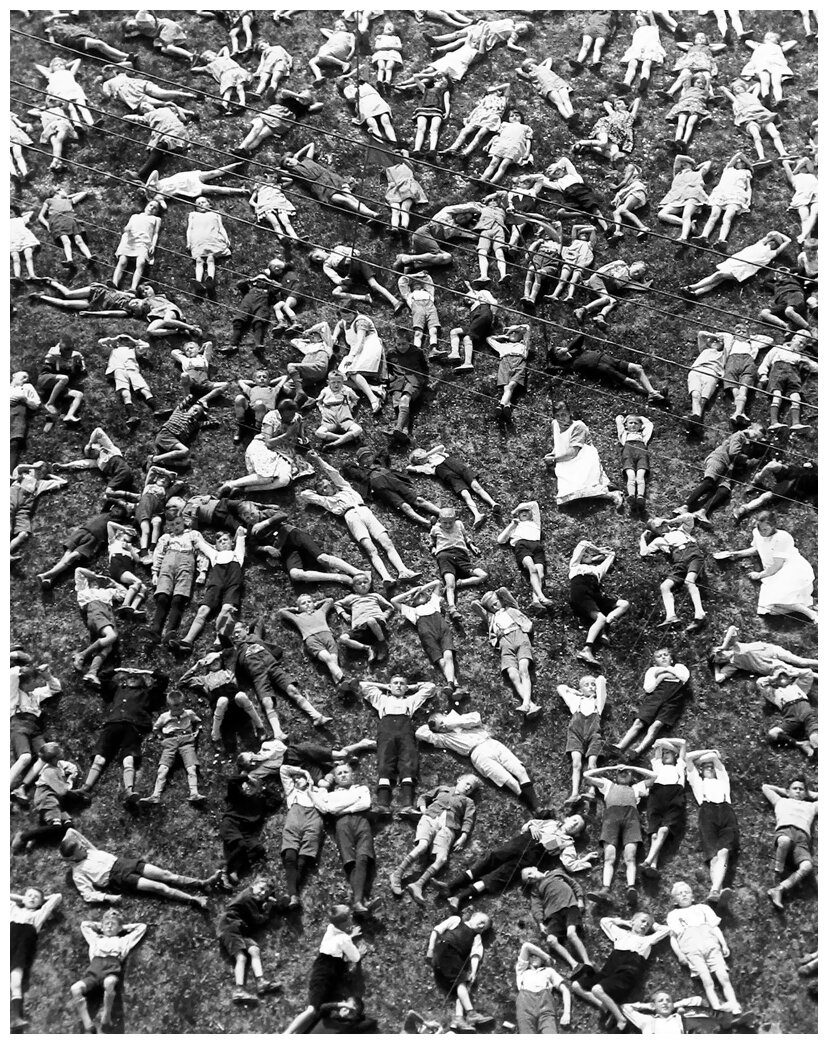

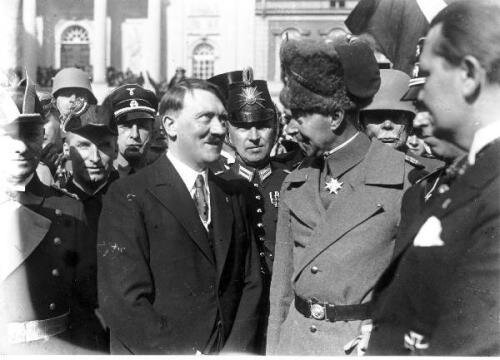

One Penguin classics edition uses a photograph by the Hungarian photographer Martin Munkácsi (who inspired the young Cartier-Bresson, and would capture a famous image of President von Hindenburg handing Germany over to Adolf Hitler on 21 March 1933). Taken in 1929, ‘Summer Camp near Bad Kissingen’ is an aerial shot of children lying on the grass. They are relaxing, or being forced to relax, with arms behind their heads, or heads propped up on one elbow. Some kids have crossed their legs or shaded their eyes; one or two have attained shavasana.

At first glance the summer idyll could be mistaken for a field of corpses. And this duck/rabbit visual shift between youth camp and death camp seems to fit the mood that Camus establishes in the opening sections of The Plague, where he evokes a town too consumed with its daily life to believe that death could come for it at such a scale.

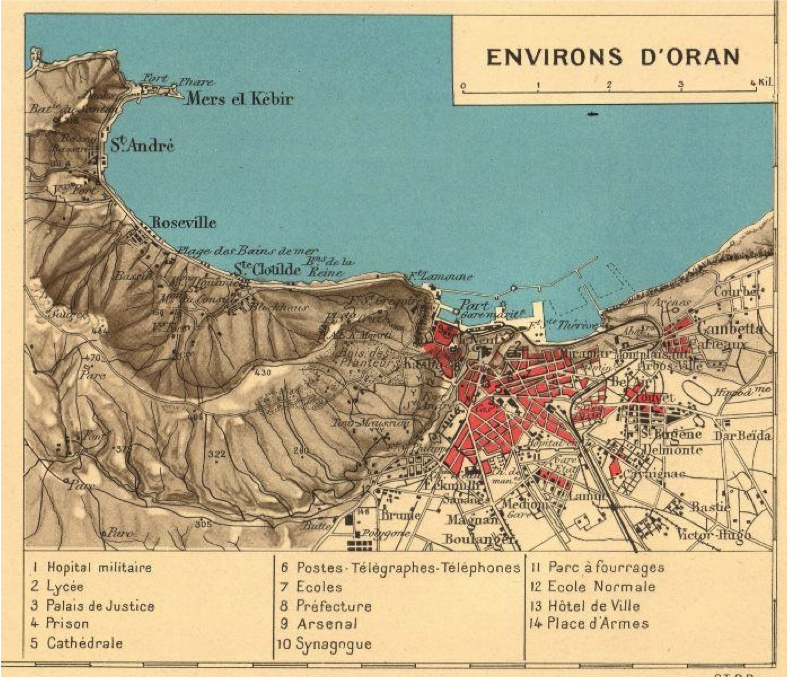

Les curieux événements qui font le sujet de cette chronique se sont produits en 194., à Oran, De l’avis général, ils n’y étaient pas à leur place, sortant un peu de l’ordinaire. À première vue, Oran est, en effet, une ville ordinaire et rien de plus qu’une préfecture française de la côte algérienne.

The opening lines stress the ordinariness of the setting, the French Algerian port of Oran where Camus arrived in 1941 for tuberculosis treatment, and where he began gathering material for the book. The first English translation, by Stuart Gilbert in 1948, gives these as follows:

The unusual events described in this chronicle occurred in 194…, at Oran. Everyone agreed that, considering their somewhat extraordinary character, they were out of place there. For its ordinariness is what strikes one first about the town of Oran, which is merely a large French port on the Algerian coast, headquarters of the Prefect of a French ‘Department’. (1)

In Robin Buss’s 2001 version, which seems to be taking fewer liberties, we have:

The peculiar events that are the subject of this history occurred in 194–, in Oran. The general opinion was that they were misplaced there, since they deviated somewhat from the ordinary. At first sight, indeed, Oran is an ordinary town, nothing more than a French Prefecture on the coast of Algeria. (5)

This short prelude introduces what is in one sense an ordinary town, an allegorical ‘everytown’. The daily routines of money and love-making, sea-bathing and newspaper reading are charted in a cool, objective, transparent style: ‘the style of absence which is’, as Roland Barthes remarked of Camus’s prose, ‘almost an ideal absence of style’ (Writing Degree Zero, 77). Further down the page are the most quotable lines, which demonstrate his way with an aphorism: ‘A convenient way of getting to know a town is to find out how people work there, how they love and how they die’ (5).

The opening section of The Plague might touch off various moments of recognition, depending on where you read it from. I find some answering echoes in Cape Town, which mirrors the latitude of Oran and was also once a colonial port. This is also business-minded, market and tourism-driven place, at least in the oversold city centre, which is also ‘ringed with luminous hills and above a perfectly shaped bay’ but ‘so disposed that it turns its back on the bay, with the result that it’s impossible to see the sea, you always have to go and look for it’ (trans. Gilbert, 3-4). As a result of high apartheid modernism (Le Corbusier in Africa), the office blocks and raised highways of Cape Town’s Foreshore cut the docks off from the city centre and funnel the summer south-easter, so that the streets are deserted ‘and only the wind moaned continually down them’: ‘A smell of seaweed and salt rose from the wind-tossed, always invisible sea. This empty town, white with dust, saturated with sea smells, loud with the howl of the wind, would groan at such times like an island of the damned’ (129-130).

Camus’s narrator suggests that there still exist towns and countries where people have now and again an inkling, or an intimation, of something different: le soupçon d’autre chose. A hint, a dash, a suspicion or smidgeon. On the whole, he goes on, it might not change their lives, but at least ‘they had an intimation, and that’s so much to the good’ (6) Oran, on the other hand, appears to be une ville sans soupçons, c’est-à-dire une ville tout à fait moderne: ‘a town without inklings, that is to say, an entirely modern town’ (6). A town in which it is not good to be an invalid: ‘Being ill is never agreeable, but there are towns which stand by you, so to speak, when you are sick; in which you can, after a fashion, let yourself go’ (6). Oran is not like that: Un malade s’y trouve bien seul: ‘A sick person is very lonely here’ (6).

Like so much else in the book, the confident simplicity of the writing is deceptive. The words let on more, betray more, and perhaps know more than their author ever intended. The ‘peculiar events’ of the novel are indeed ‘not in their place’. They are misplaced in a complicated and painful sense, with major consequences for how one interprets the book, and whether the great humanist credo that it arrives at can be believed in: pour dire simplement ce qu’on apprend au milieu des fléaux, qu’il y a dans les hommes plus de choses à admirer que de choses à mépriser: ‘to say simply what it is that one learns in the midst of such tribulations, namely that there is more in men to admire than to despise’ (237).

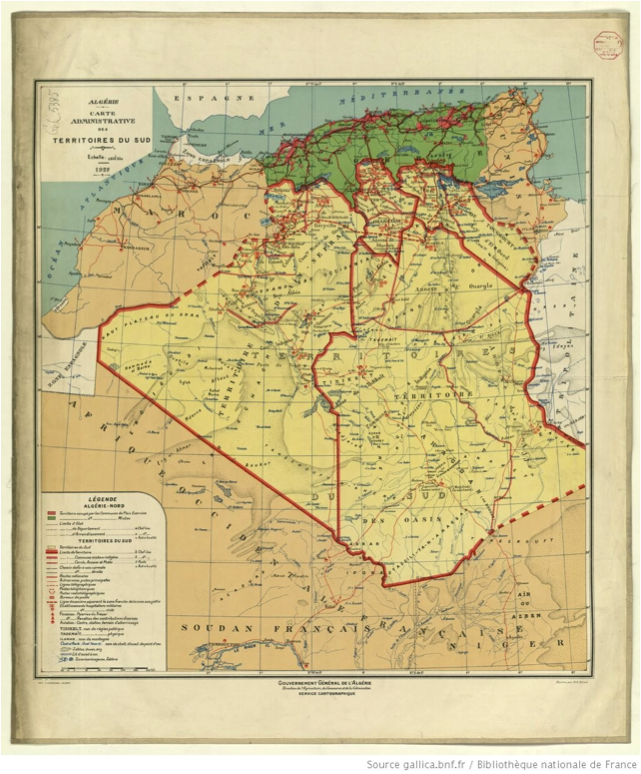

The opening lines of The Plague contain, in embryo, the whole problem of a literary work that tempts you to read it as kind of universal fable, an allegory of human suffering, stoicism and resistance – but also stubbornly refuses to give up its allegiance to, and imaginative possession of, an actual place. Today the port of وهران (Oran or Wahrān) is the second-largest city in Algeria, with a population of around a million people. In nineteen forty something, it was the town with the biggest population of French Algerians, or pied noirs (of which Camus, born 1913 in Algiers, was one). The pejorative term, ‘black feet’, was possibly derived from the boots of the French army which began the conquest and ‘pacification’ of this vast north African territory in 1830: a brutal imperial venture notorious for the military strategy of razzia and ratissages – punitive raids on Algerian villages, literally a ‘raking over’.

And why the blank in 194–? The convention is more common for proper names, signifying someone or somewhere familiar to the author but lightly or partially disguised for the reader. It is really Oran itself that the opening lines should have rendered as O–. That might have avoided some difficulties. Because when you try to place the book – to properly situate it in its historical moment, and in north Africa – The Plague becomes a deeply complex, even contradictory work: one that that absorbs and reflects back as much history and difficulty as the reader is willing to bring to it.

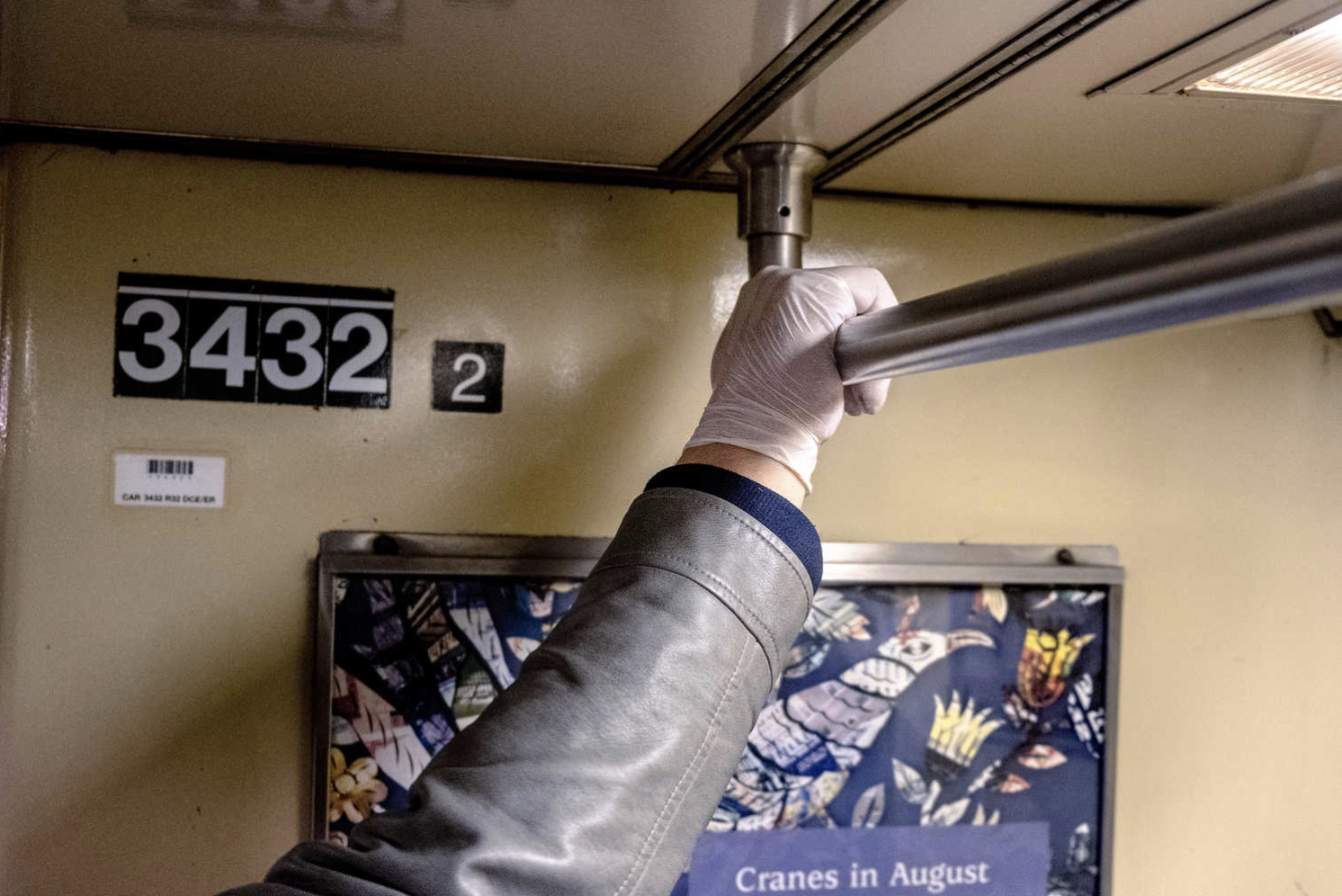

What follows (written in the dog days of lockdown) is an account of reading Camus’s book over many years, in the midst of various real-world epidemics – HIV/AIDS, Ebola, COVID-19 – and from a place, South Africa, that emerges as a kind of mirror image of the north Africa in which the novel is set. Or else just a confusing mirage.

2.

‘On the morning of April 16, Dr Bernard Rieux emerged from his consulting-room and came across a dead rat in the middle of the landing’. This sentence at the start of chapter two could also be a workable first line. The Plague has a double beginning in this sense. We move from the distant, generalised register of the first chapter into the mesh of individual human lives and destinies. It begins once as kind of moral fable, and then again as a medical thriller.

The five movements of the The Plague generally follow this structure: first a brief prelude in the voice of collective opinion (de l’avis général), then the dive into plot. Like the overture to an opera (and the book does contain one: Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice), the preludes introduce general thematic ideas that will then play out in actual human lives and bodies. The exception is the third movement, when the plague is at its height, which is narrated entirely in the voice of generalised experience.

As soon as we leave Rieux’s consulting room, we meet the old concierge, M. Michel, who is convinced that the dead rats are some kind of practical joke – this is Patient Zero, perhaps. Dr Rieux is the main character; in fact he is also the narrator, but we only learn that towards the end of the book. For now (if we stay within the realist frame), he is narrating his experience in the third person, while also explaining how it is that he has the authority to tell the story:

Of course a historian, even if he is an amateur, always has his documents. The narrator of this history has his documents: first of all, his own testimony, then that of others since, by virtue of his role in this story, he came to collect the confidences of all the characters in it; and, finally, he had written texts which he happened to acquire. He intends to borrow from them when he sees fit and to use them as he wishes. He intends…But perhaps it is time to have done with preliminaries and caveats, and turn to the story itself. The narrative of the early days must be given in some detail. (8)

Here is the punctilious, rather pedantic tone, giving us fiction packaged as documentary. It is a device which goes right back to the beginning of the English novel. The prefaces to Robinson Crusoe do exactly the same thing: impersonating non-fiction to promise a ‘just history of fact’. Defoe wrote his own Journal of the Plague Year, of course, which purports to be an account by a survivor of the 1665 outbreak in London, but is actually another faked autobiography: ‘as close to a forgery of an historical document as one can get without beginning to play with ink and old paper’ (Coetzee vii).

After this briefing on the factual basis of what we are about to read, the rest of part one records the ‘troubling signs’ of the approaching epidemic, while also introducing us to the five main characters. The narrator is like a midfielder moving the ball quickly and accurately around the football pitch – perhaps in the Spanish style of swift, accurate passing that replaces individual showboating for a dogged collective effort (Camus was a keen player and there is some football chat in the book. At one point we hear that ‘there is no finer place in the team than a midfielder’: ‘the centre-half is the one who positions the game and that’s what football is about’ (113). Though Camus himself took on the greater moral anguish of being goalie.)

First we meet the journalist Raymond Rambert. He is stranded in Oran while on assignment and missing his lover back in Paris. Camus, who obviously split off portions of himself into his ensemble cast, was similarly stuck when he went to central France to recuperate from TB in 1942. With the Allied landings in north Africa in November of that year, the German army occupied the south of France to secure the Mediterranean coastline. Camus was sealed off from his wife and from Algiers (which would become, in a curious turn of colonial history, the de facto capital of Free France when the Allied high command was based there).

In letters Camus described The Plague as emerging from a struggle for breath; it was also, he said, a response to a world without women. It is certainly a very male book (but not, I think, a masculinist one) and largely sexless. Dr Rieux’s wife (unnamed) leaves Oran just as the story begins. She is going to a sanatorium out of town for treatment; they bid farewell at the train station, promising to make a fresh start on her return. Her place is taken by Rieux’s mother, a watchful, largely silent presence who helps take care of her son and his apartment during the epidemic.

Madame Rieux’s stoic silence must hold something of Camus’s own mother, Catherine Hélène Sintés, who lost her husband in the First World War and during Albert’s childhood cleaned houses in the working-class district of Belcourt.

Catherine Camus was illiterate, partially deaf, with a speech impediment that meant she hardly spoke. When her son died in a car accident in 1960, age 46, a briefcase containing a manuscript titled Le premier homme (The First Man) was retrieved from the wreck. Only brought into print in 1994 (by Camus’s daughter Catherine), The First Man evokes a colonial, French-Algerian childhood in all the historical texture, social detail and depth of field that seems so absent from The Plague. Camus had dedicated his unfinished manuscript to his mother: To you who will never be able to read this book.

There is a curious moment just as Rambert is introduced. He tells Rieux that he is ‘doing an investigation for a large Parisian newspaper about the living conditions of the Arabs’ and wants information on their health situation (11). Rieux asks the journalist if he can tell the whole truth, by which he means ‘an unqualified indictment’ (condamnation totale). Rambert replies: ‘Unqualified? No, I have to say I can’t. But surely there wouldn’t be any grounds for unqualified criticism?’:

Rieux gently answered that a total condemnation would indeed be groundless, but that he had asked the question merely because he wanted to know if Rambert’s report could be made unreservedly or not.

‘I can only countenance a report without reservations, so I shall not be giving you any information to contribute to yours.’ (11-12)

Why does the narrator raise the question of ‘the Arab quarter’ only to ignore it? For the rest of the work the colonial predicament of Oran is pushed to the edges of the text’s awareness; the lives of its Arabic, Muslim and African inhabitants will surface only rarely and obliquely, unsettling the workings of the allegory.

Next we meet Jean Tarrou, a newcomer to Oran, living in a hotel in the city centre and a great lover of swimming. He keeps a notebook, and this is one of the documentary sources that the narrator employs. In counterpoint to the growing tension of the plague plot, Tarrou’s notebooks, with their ‘deliberate policy of insignificance’ (21), work to lighten the atmosphere. With an eye for the absurdity of everyday life, they record chance details and snippets of overheard talk.

Tarrou records how each day an old man comes out onto the opposite balcony, tears up bits of paper and scatters them over the edge, while calling to the cats in the side-street. When they come out and lift their paws towards this shower of white butterflies, he spits on the cats, ‘firmly and accurately’: ‘When one of his gobs of saliva hit the target he would laugh’ (22). Elsewhere, Tarrou proposes a kind of mock serious urban fieldwork reminiscent of Georges Perec and the Situationists:

‘Question: how can one manage not to lose time? Answer: experience it at full length. Means: spend days in the dentist’s waiting room on an uncomfortable chair; live on one’s balcony on a Sunday afternoon; listen to lectures in a language that one does not understand, choose the most roundabout and least convenient routes on the railway (and, naturally, travel standing up); queue at the box-office for theatres and so on and not take one’s seat; etc.’ (22)

Camus’s prose, wrote one early reviewer, was ‘like Kafka written by Hemingway’ (cited in Todd, 155). Tarrou’s vignettes help to activate a Kafkan strain of absurdism and dark comedy in The Plague. We watch as city authorities fuss over what to call the epidemic and attempt to deal with it in laughably managerial, bureaucratic ways.

We also get a reverse-angle portrait of the doctor-narrator when we read a quoted description of Rieux: ‘He is absent-minded when driving and often leaves his car’s indicators up even after he has taken a bend. Never wears a hat. Looks as if he knows what’s going on’ (25). This is like the mirror in a Van Eyck portrait: we catch a glimpse of the artist, reflected back in the course of depicting his main subjects: ‘As far as the narrator can judge, it is quite accurate’ (25).

The diaries are also performing another, as yet undisclosed role in the book. Tarrou, who becomes a close friend of Rieux, will die of the plague, taken cruelly just as the epidemic is ebbing. So the passages which the doctor copies into his chronicle are also a kind of memorial and elegy for a lost comrade. This wry ‘anthology of insignificant acts’ is edged by unspoken loss and grief.

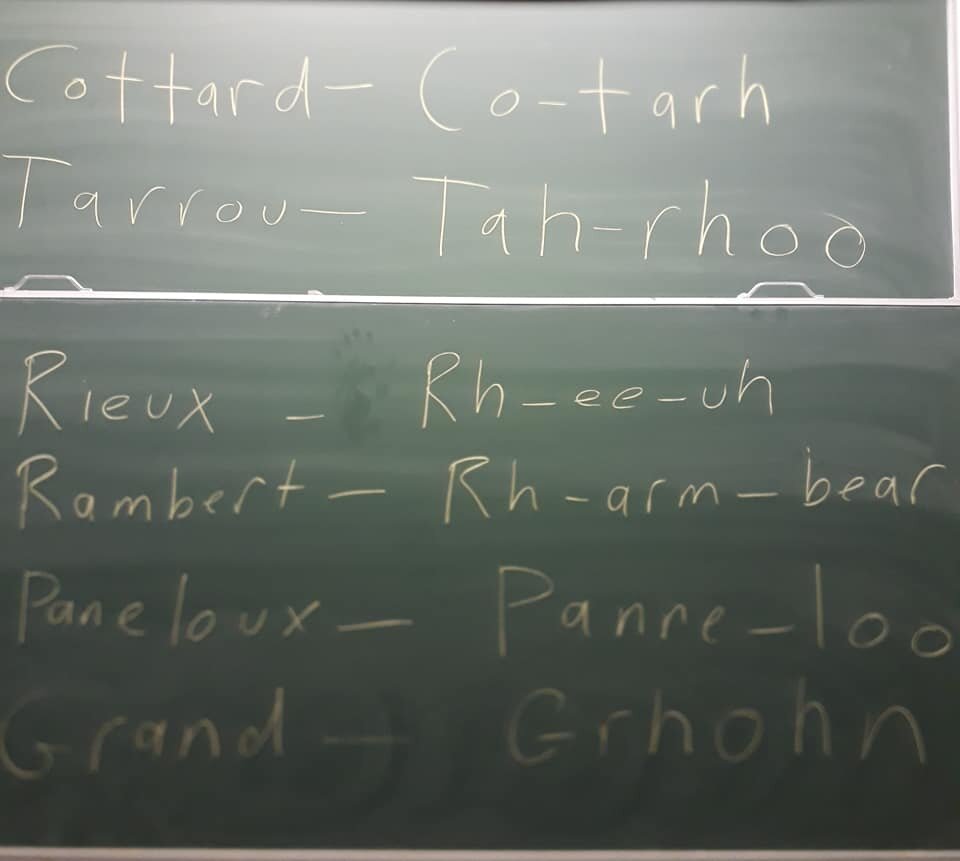

The three other main characters are Father Paneloux (a Jesuit priest), Cottard (a shady character, probably a criminal, a man with something on his conscience) and Joseph Grand, an ironic name for a small, mild-mannered municipal clerk who tends to speak in clichés. We gradually learn (even though he is very secretive about it) that Grand been at work on a novel for years, but never managed to get past the first line: ‘On a fine morning in the month of May, an elegant woman was riding a magnificent sorrel mare through the flowered avenues of the Bois de Boulogne’ (80).

‘What do you think of it?’ he asks Rieux after divulging his secret and reading it aloud, while the sounds of curfew and civil unrest reach them through the windows (81). Rieux says diplomatically that the beginning makes him curious to know what will follow. Grand slaps the manuscript with exasperation:

‘That’s only a rough idea. When I have managed to describe precisely the picture that I have in my imagination, when my sentence has the very same movement as the trotting horse, one-two-three, one-two-three, then the rest will be easy and above all the illusion will be such from the very start that it will be possible to say: “Hats off, gentlemen!”’ (81)

A desire for a total and perfect mirroring, or mimesis, of the world in language: the very worst way to set about writing anything. The stuckness and stasis of Grand’s manuscript is literary microcosm for the suspended animation of the town: the same films are shown on a loop; the same blues records spin round in the cafes (I went down to St James Infirmary / Saw my baby there…). The stranded opera company puts on the same Gluck tragedy each evening (at least until Orpheus falls down on stage, struck down by the plague in the middle of an aria).

Nonetheless, Grand will emerge as the unlikely hero of the book: the person who takes a major role in organising the health teams that fight the epidemic. When he falls ill in Part IV and tells Rieux to burn his manuscript (which is just page after page of crossed-out first lines), we finally break out of the frustrated plotting and narrative cul-de-sacs that detain us so long in the middle of Camus’s novel. Grand unexpectedly recovers and begins a letter to his estranged wife. The plague graph begins to fall and we move towards a denouement: literally the ‘unknotting’ of the destinies of five solitary men – Rieux, Rambert, Tarrou, Grand, Paneloux – who all come to a greater understanding of human solidarity.

So: a novel within a novel, a diary within a diary, a tragedy within a tragedy – The Plague, which starts out by claiming to be an objective chronicle, is actually a hall of mirrors.

3.

A man is sitting in his car at an intersection when suddenly his field of vision goes white. The doctor who treats him also goes blind, and before long the ‘white sickness’ goes global. So begins José Saramago’s 1995 novel Ensaio sobre a cegueira (published as Blindness in English). When reluctantly selling the film rights, Saramago insisted that the city remain unidentified (in the movie it becomes a digital composite of Toronto, Tokyo and São Paulo) and the characters nameless: ‘The girl with the dark glasses’, ‘The boy with the squint’, and so on.

Directed by Fernando Meirelles, the 2008 adaptation is not an easy watch. The sufferers are quarantined in a derelict asylum where all human decency soon breaks down into violence, intimidation, rape and the rule of the strong. We watch Mark Ruffalo and Julianne Moore feeling up walls and tripping over things for two hours. Her character is actually pretending to be blind in order to accompany her husband into quarantine; but in fact everyone on screen looks like they’re playacting. Unsure about the blurry placelessness and heavy seriousness of the film, New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott wrote that in Blindness ‘human civilisation is threatened by a sudden and virulent outbreak of metaphor’.

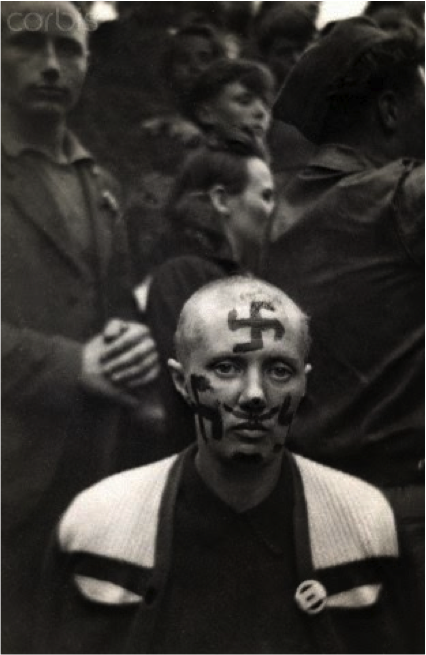

It’s tempting to use the same quip about Camus’s work. On publications, La peste was immediately read as an allegory for the ‘brown plague’ of Fascism in Europe, as well as the questions of resistance, collaboration and genocide that consumed post-war France. For a friend who had been in the concentration camps, Camus inscribed a copy: ‘To a survivor of the plague’. In his notebooks he suggested that the book ‘may be read in three different ways’:

It is at the same time a tale about an epidemic; a symbol of Nazi occupation (and incidentally the prefiguration of any totalitarian regime, no matter where), and thirdly, the concrete illustration of a metaphysical problem, that of evil. (Cited in Todd 168).

This symbolic response to historical events has always had its detractors. ‘Camus’s world is one of friends, not of fighters’, wrote Roland Barthes, who found its ‘ahistorical ethic’ troubling (‘La peste’, 544). Simone de Beauvoir felt that to equate the occupation with a natural scourge was ‘a way to escape History and real problems’, and as a result ‘everyone agreed too easily with the disembodied moral emerging from that parable (cet apologue)’ (La Force des choses 144). As Tony Judt points out in his 2001 introduction, this accusation still surfaces in academic treatments of Camus: ‘he lets Fascism and Vichy off the hook, they charge, by deploying the metaphor of a “nonideological and nonhuman plague”’ (Judt xiv, quoting Dunn 150).

The most extensive version of this critique that I have found comes from Fredric Jameson, who writes that this ‘slippage’ between Nature and History ‘emerges as a full-blown ideology when the Nazi historical project is represented through the content of that very different thing, a seething bacterial epidemic that intervenes in the web of private human destinies to terminate them in unjustifiable and properly absurd extinction’ (307). He goes on:

Indeed, this slippage between two distinct perspectives – the one proposing a political and historical analysis capable of energizing its spectators for change and praxis even in the most desperate historical circumstances; while the other perpetuates some ultimately complacent metaphysical vision of the meaninglessness of organic life, to which the response, at best, can only be some private ethical stoicism of a ‘myth of Sisyphus’ – the contamination of two incompatible languages has increasingly, in our own time, been identified as one dangerous source of depoliticization. (307-308)

Reading this kind of critique, expressed in this kind of language (slippage, praxis, contamination, depoliticization) I wonder: how can this strain of Marxist literary criticism be, on the one hand, so smart, perceptive, rigorous; and on the other hand, so reductive about how literature actually works on its audience? Are the languages of the sociohistorical and the metaphysical really so incompatible? Is the vision of private stoicism really so ‘contaminating’ to social thinking?

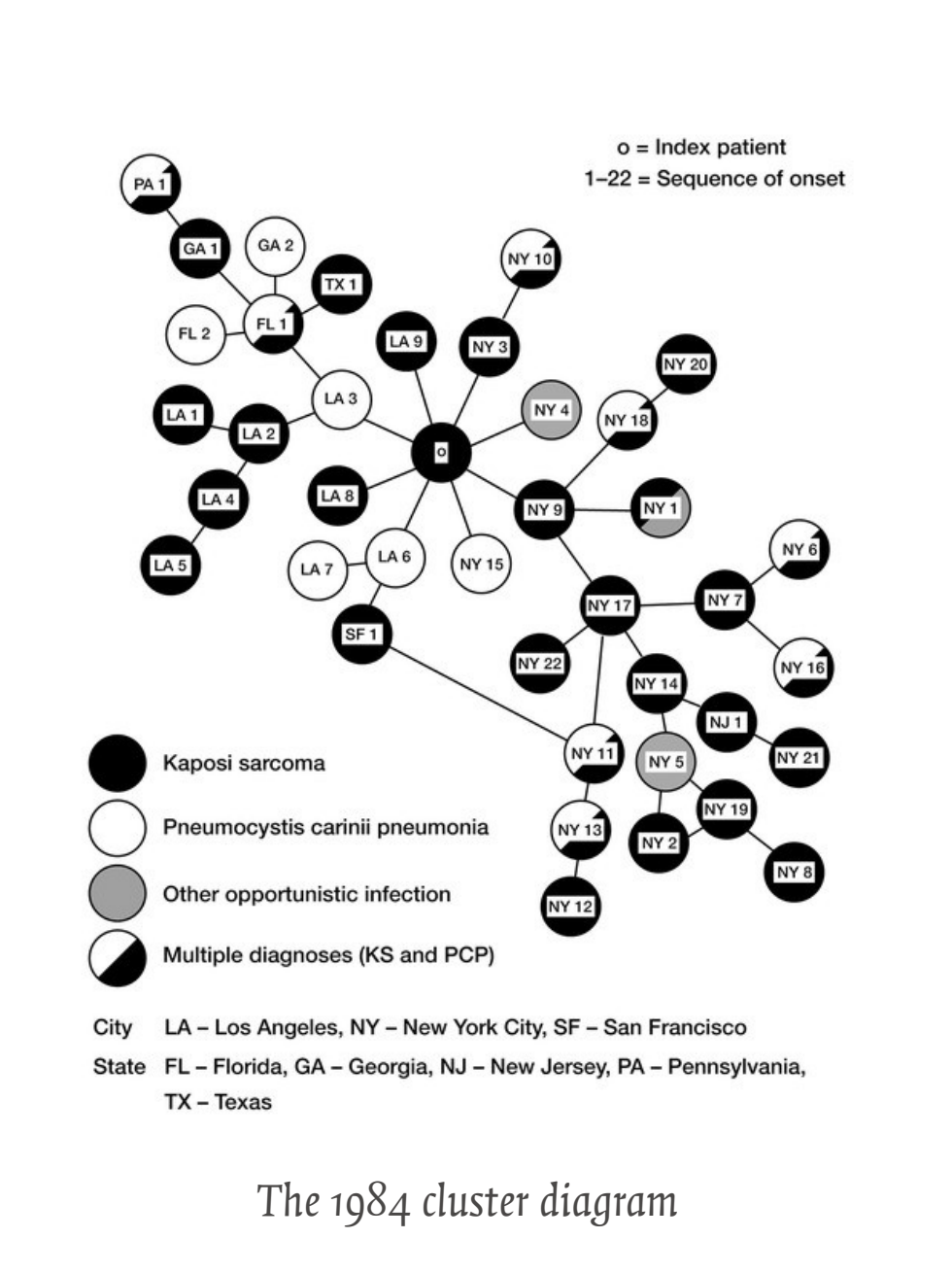

If it’s wrong to transmute historical events and agents into a metaphorical plague, one can also level the criticism from the other direction: it’s wrong to make the very real suffering of disease serve as a symbol for anything other than itself. ‘My point is that illness is not a metaphor’ wrote Susan Sontag in her 1978 discussion of TB and cancer, ‘and that the most truthful way of regarding illness – and the healthiest way of being ill – is one most purified of, most resistant to, metaphoric thinking’ (‘Illness as Metaphor’). The work had emerged, in part, from her regret over describing Western imperialism as a ‘cancer’. Ten years later, she extended the argument to HIV/AIDS: ‘The age-old, seemingly inexorable, process whereby diseases acquire meanings (by coming to stand for people’s deepest fears) and inflict stigma is always worth challenging […] With this illness, one that elicits so much guilt and shame, the effort to detach it from loaded meanings and misleading metaphors seems particularly liberating, even consoling’ (‘AIDS and its Metaphors’).

In my view, none of the above charges really stick when applied to a work as clear-eyed and self-aware as The Plague. If imagining the Nazi occupation as a seething bacterial epidemic blurs the question of accountability, then perhaps this is because Camus’s work is suspicious of identifying and blaming too quickly. Or of allowing blame to dominate other, more diffuse questions about everyday accommodations to suffering and tyranny that do not resolve into the easy binaries of victim and perpetrator. In his reflections on ‘Paris Under the Occupation’, Jean-Paul Sartre remembered the ‘instinctive humanitarian helpfulness’ that French citizens would find themselves showing to German soldiers, even while opposing Nazism:

We remembered the command we had given ourselves once and for all: don’t ever speak to them. But, at the same time, faced by these lost soldiers, an old humanitarian willingness to help awoke in us, and another command that went back to our childhood and which enjoined us to not ever leave a person in difficulty. Then, according to one’s mood and the occasion, one decided to say: ‘I don’t know’ or ‘Take the second street on the left’ and in both cases, one left unhappy with oneself. (3)

Granted, it is odd to read Camus’s response to France’s wartime experience and find no outright villains. Even Cottard, the shady criminal type who thrives under the plague, is treated with a kind of tenderness. In the closing moments of the book, as we see him go down under the fists of the police, one senses Camus’s scepticism about a post-war climate where individuals were being shamed as collaborators, sometimes becoming scapegoats whose publicly advertised crimes might have worked to draw attention away from more subtle and widespread forms of complicity.

As for the question of using disease as metaphor: on one plane the work does full naturalistic justice to the horrors of bubonic plague itself, and the long history of the bacillus Yersinia pestis in human affairs (so long that the word ‘plague’ is, of course, inescapably metaphorical). In the book-length version of Illness as Metaphor, Sontag actually exempts The Plague from her critique. The work, she says, is not really a political allegory:

Camus is not protesting anything, not corruption or tyranny, not even mortality. The plague is no more or less than an exemplary event, the irruption of death that gives life its seriousness. His use of plague, more epitome than metaphor, is detached, stoic, aware – it is not about bringing judgment. (147-8)

The sober narrator is all too aware of the rush to judgment that the plague brings, most obviously in the sermon by Father Paneloux. The Jesuit priest interprets the pestilence (in time-honoured religious fashion) as the language of God’s displeasure: ‘Calamity has come on you, my brethren’, he begins, ‘and, my brethren, you deserved it’ (73). In the book’s even-handedness, though, Paneloux is also a sympathetic character; or, at least, not a caricature (still no easy villains). Paneloux has made a study of Augustine (like Camus himself, who wrote a thesis on this Algerian saint). And the second sermon he gives is a much more complex and compelling justification of religious faith. It is a chapter in which one can sense Camus wanting to give full weight to the spiritual counter-argument to his own secular vision. A much fuller weight than that given, for example, to the priest in The Outsider, none of whose certainties, says Meursault, ‘was worth one strand of a woman’s hair’ (118).

The Plague, in other words, does not take the easy way out by imagining the worst. It does not scapegoat, nor does it tend towards the complete breakdown of social order that we see in Blindness and the many stories of apocalypse that modern human societies like to feed themselves: stories in which civilisation is revealed to be (as the aspiring but cliché-ridden novelist Joseph Grand might have said) ‘just a thin veneer’.

In an early chapter, Rieux stands at the window looking out at the town, both indulging and resisting the aura surrounding the word ‘plague’. ‘A word that conjured up in the doctor’s mind not only what science chose to put into it, but a whole series of fantastic possibilities utterly out of keeping with that grey-and-yellow town under his eyes’ (trans. Gilbert 37):

A tranquillity so casual and thoughtless seemed almost effortlessly to give the lie to those old pictures of the plague: Athens, a charnel-house reeking to heaven and deserted even by the birds; Chinese towns cluttered up with victims silent in their agony; the convicts at Marseille piling rotting corpses into pits; the building of the Great Wall in Provence to fend off the furious plague-wind; the damp, putrefying pallets stuck to the mud floor at the Constantinople lazar-house, where the patients were hauled up from their beds with hooks; the carnival of masked doctors at the Black Death; men and women copulating in the streets of Milan; cartloads of dead bodies rumbling through London’s ghoul-haunted darkness – nights and days filled always, everywhere, with the eternal cry of human pain. No, all those horrors were not near enough as yet even to ruffle the equanimity of that spring afternoon. The clang of an unseen tram came through the window, briskly refuting cruelty and pain. Only the sea, murmurous behind the dingy chequer-board of houses, told of the unrest, the precariousness of all things in this world. (trans. Gilbert 38)

Occasionally the restrained, even pedantic narrative voice gives way to rhetorical set pieces like this. One can sense Camus the lyrical essayist seizing the controls from his alter ego Dr Rieux. But the passage conjures up these nightmarish images – culminating with the plague-fires described by Lucretius, where Athenians fight each other with torches on the seashore to secure a space for the funeral pyres of their loved ones – only to set such visions aside.

Most of the time, La peste offers something much less sensational, much more humdrum: a lockdown, sometimes terrifying, but often just boring and frustrating, that we all have to get through after our own fashion: ‘The trouble is, there is nothing less spectacular than a pestilence and, if only because they last so long, great misfortunes are monotonous’ (138).