Reading, writing, walking the South African highway.

Social Dynamics 43:1 (2017).

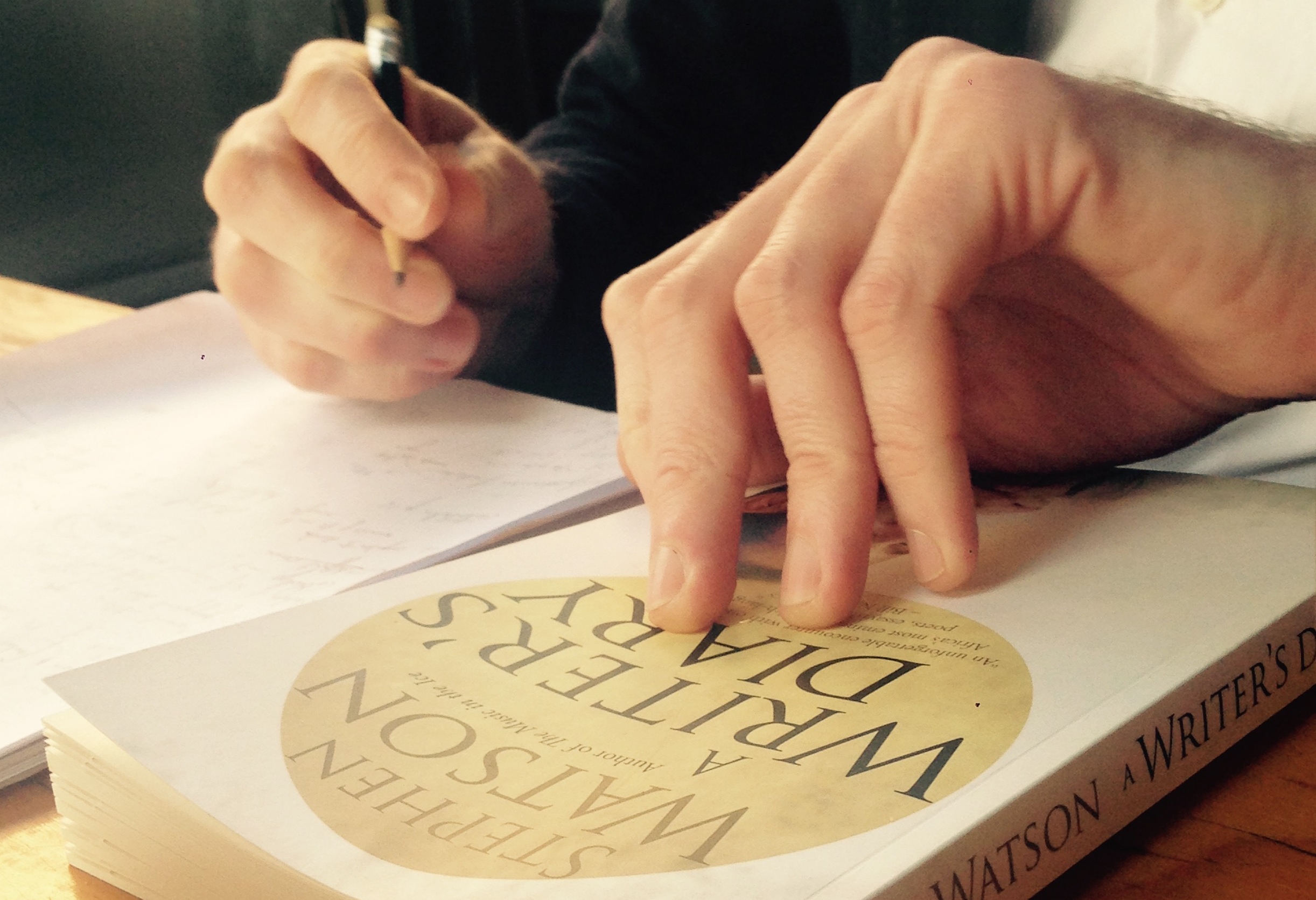

Less academic version appears as 'Thirteen Ways of Looking at the N2' in Firepool.

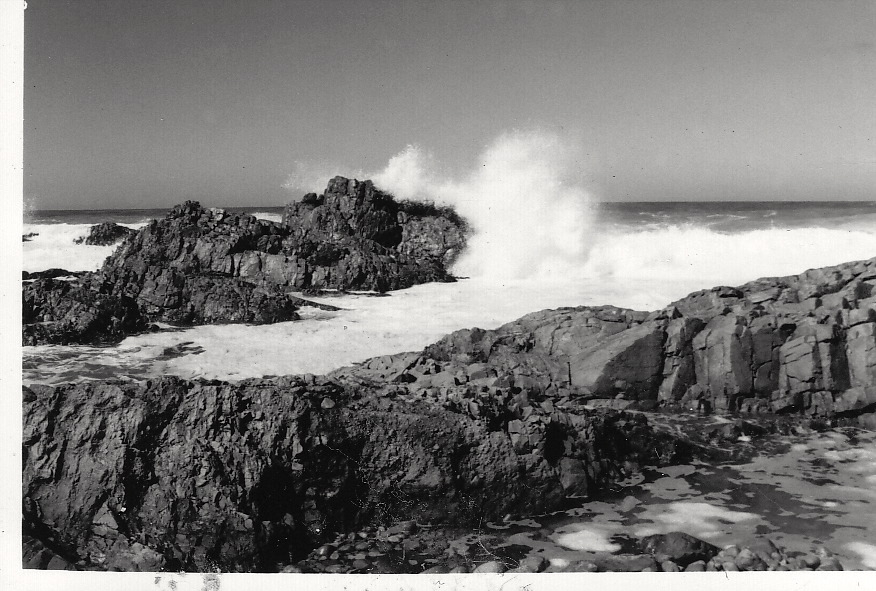

N2. Curled up in that tiny alphanumeric are thousands of kilometres, hundreds of service stations, millions of tons of concrete. N2 can mean a London bus route; an intelligence officer in the US Navy; an anti-nuclear song by the Japanese indie group Asian Kung-Fu Generation. But for my purposes it is the longest highway in South Africa, which starts at an unfinished flyover near the docks in Cape Town, follows the eastern seaboard of the country (roughly) for over 2 000 kilometres, then bends north and west below Swaziland to end at the town of Ermelo in the province of Mpumalanga.

Major highways are not thought about much. They are pieces of infrastructure that (if working as intended) efface themselves, receding from view in the mirror. In his hidden history of the UK’s motorway system, Joe Moran suggests that this bland corporate terrain of tarmac, underpasses and thermoplastic road markings is ‘the most commonly viewed and least contemplated landscape’ in Britain: ‘The road is almost a separate country, one that remains under-explored not because it is remote and inaccessible but because it is so ubiquitous and familiar.’

Perhaps because of the late age at which I (after many failed attempts) got my driver’s licence, piloting vehicles along strips of tarmac has never quite lost its strangeness for me, and the psychology and social behaviours associated with driving are, I believe, complex and neglected domains. With the passing of the era of cheap oil, future humanity will look back on our cities with wonder, disbelief and disgust at how totally urban spaces were shaped around the velocities and demands of the private vehicle. So, an important strategy for environmental writing in the 21st century might be to estrange the practice of everyday life, to conduct an anthropology not of the distant and exotic, but rather of the near, the mundane, the everyday.

‘What speaks to us, seemingly,’ wrote Georges Perec in 1973, ‘is always the big event, the untoward, the extraordinary: the front-page splash, the banner headlines. Railway trains only begin to exist when they are derailed, and the more passengers that are killed, the more the trains exist. Aeroplanes achieve existence only when they are hijacked. The one and only destiny of motorcars is to drive into plane trees.’ But, he goes on, in our haste to measure ‘the historic, significant and revelatory, let’s not leave aside the essential: the truly intolerable, the truly inadmissible. What is scandalous isn’t the pit explosion, it’s working in coalmines. “Social problems” aren’t “a matter of concern” when there’s a strike, they are intolerable twenty-four hours out of twenty-four, three hundred and sixty-five days a year.’

Read more...