Seismic surveys, oceanic noise and submarine listening.

Excerpt from Sounding Environments (with Aragorn Eloff) in The Routledge Handbook of Environmental History. Edited by Emily O'Gorman, William San Martín, Mark Carey, Sandra Swart. December 2023. Outtakes.

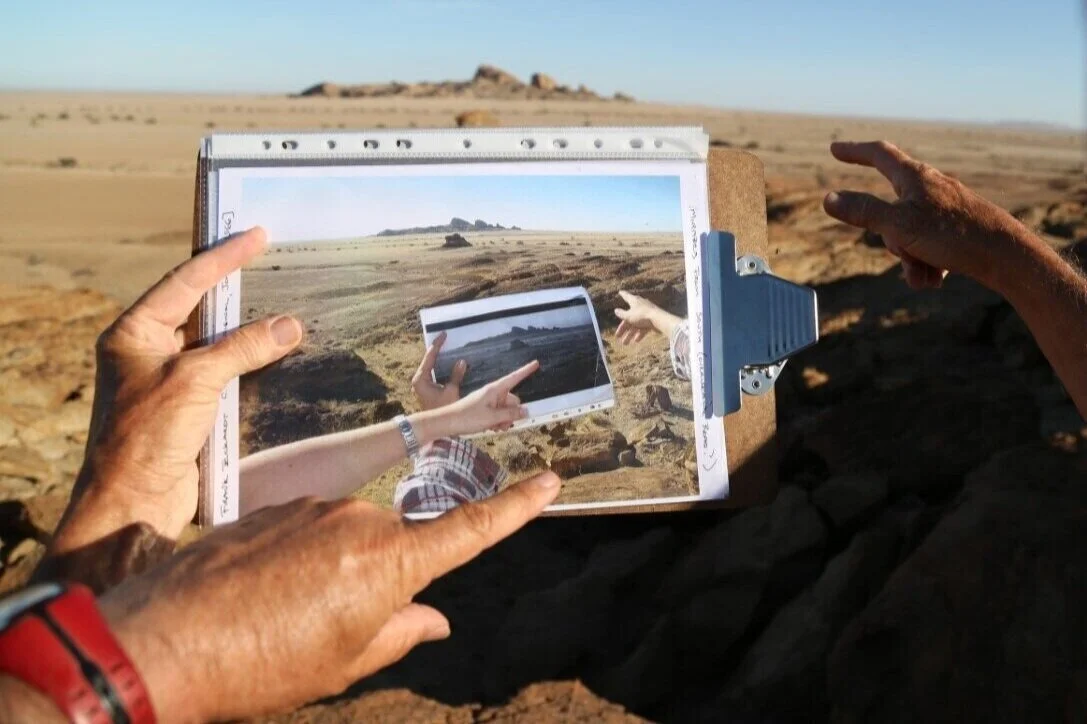

‘I am not prepared to mourn my coastline’ – in her director’s statement for the 2018 sound and video work Becoming Visible, Janet Solomon discusses her attempt to represent the acoustic violence unleashed by seismic surveys off the southern African coastline. Launched by the South African government in 2014, Operation Phakisa (to ‘hurry up’ in Sesotho) aims to ‘unlock the economic potential’ of the country’s maritime territories (more than double its terrestrial size) and to develop the ‘blue economy’. With this comes, Solomon writes, ‘an escalating and unrelenting push for oil and gas development along the east coast of South Africa’ (2018). The KwaZulu-Natal coastline, she goes on, experienced its highest ever recording of whale strandings during and after a 2016 marine seismic survey looking for oil and gas reserves, a survey granted an extension into the whale migration season.

Working via multi-channel video and sound, Becoming Visible seeks to bring home the effects of the multi-beam bathymetric sonar used to establish the topography of the sea floor. This is a method involving towed arrays of air guns, which issue pulses of over 200 decibels every ten seconds, for 24 hours a day (human eardrums typically burst at 160 decibels). The challenge presented by the work is its invitation for human listeners (with hearing evolved in the medium of air) to comprehend the very different sonic environment of a watery, submarine space. Soundwaves behave differently below the ocean surface (where hydrophones pick up the same level of sound 12 kilometres away from sources as from two kilometres away). They are faster, more far-reaching and less avoidable for marine organisms (who ‘hear’ with their whole body) even while going (to human ears) largely unheard. How then can regulatory frameworks and environmental impact assessments be extended into worlds set apart from or beyond the human sensorium? Who is listening for, or to, our companion species in the oceans?

Read More