Rereading Dugmore Boetie’s Familiarity is the Kingdom of the Lost.

Excerpt from Experiments with Truth in the Johannesburg Review of Books. 1 April 2019.

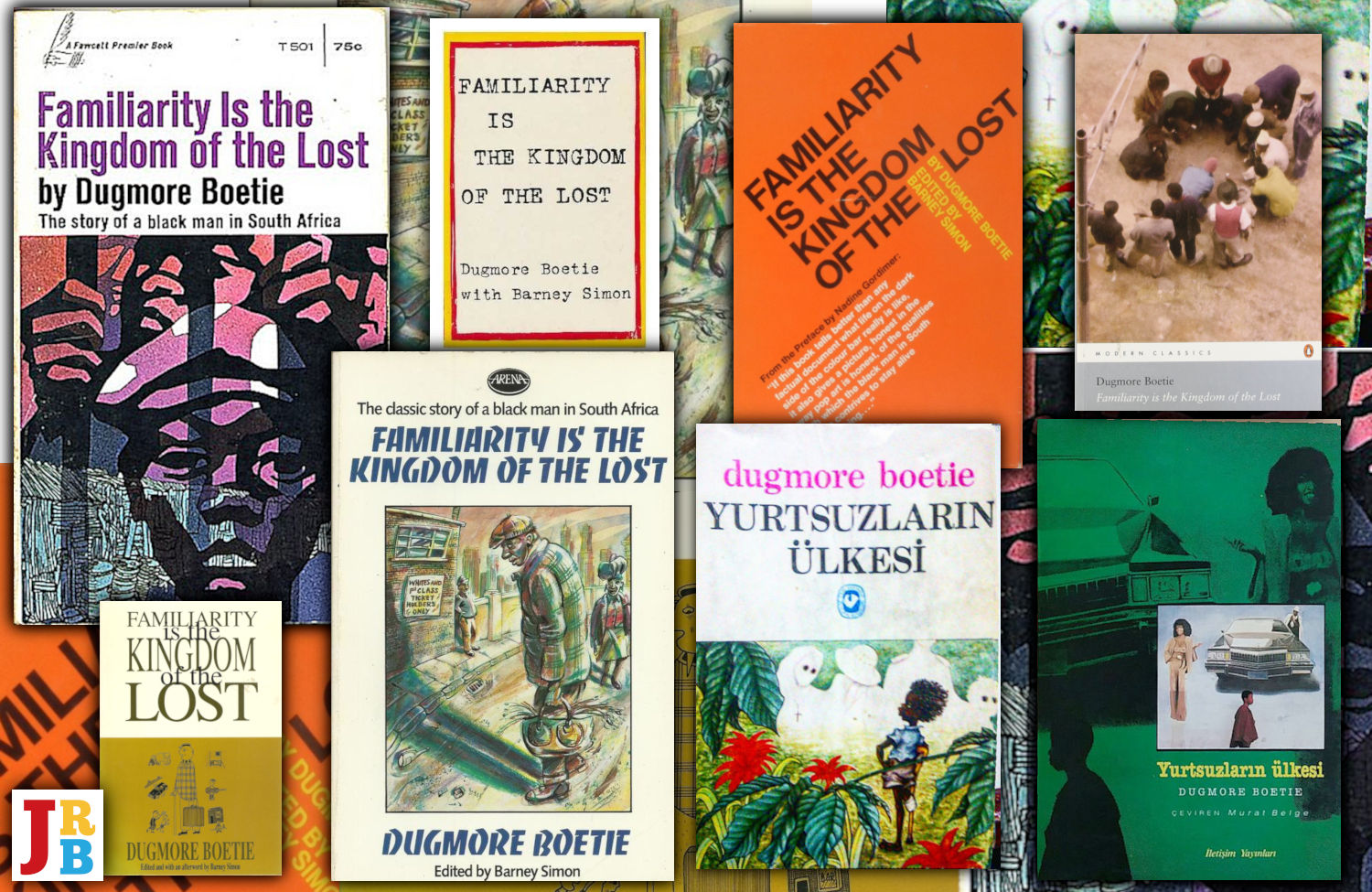

(With thanks to Jen Malec and JRB for image / montage of book covers.)

‘Is this Long Street?’

Everybody knows Long Street, so why was I being asked this by a large man who came out of a side alley?

As I began to give a cautious yes, the large man was shooed away by a smaller man in a high-vis jacket that read CCID (City Centre Improvement District).

‘They know you like to talk, Nigerians’, he said: ‘Be aware’.

Further down, the CCID had set up some large screens on which you could watch CCTV footage (taken by cameras on Long Street) of people being mugged, pickpocketed and scammed. The jerky black and white clips had been edited into a range of informative segments. The dangers of the open bag or the visible iPhone; lightning fast card swaps by people offering help at cash machines. A more elaborate version of this is the ‘false pop up’. Fraudsters tell tourists that they need a special permit to walk down a street, since it is closed for a film shoot, but that that this can easily be obtained from the nearest ATM, and let me help you with that.

There was also footage of the Shoe Scam – a ‘man particular’ con – which a friend of mine had just recently been a victim of. Staggering along drunk at night, he suddenly had someone beside him saying ‘Hey brother, we’ve got the same shoes!’, grabbing him by the shin, pulling up his trouser leg and comparing sneakers. This, the video explained, was a textbook diversion and desensitisation technique. It draws attention to the shoes with one hand while the other snakes round to remove a wallet, which is then swiftly passed it to an accomplice walking in the opposite direction.

Long Street was closed to traffic for the evening, and a crowd had gathered. People were mesmerised: to see something so furtive and fast captured in the grainy footage. To see the obliviousness, the ease, the skill of it, the way pickpockets moved when in the act, so that even the rest of their bodies seemed unaware of what the one frantic hand was doing. The woozy surprise and confusions of the marks, then the sudden realisations – it was all there in archival black and white, ‘Recorded at 00:43 a.m. on Long Street’. The footage was so transfixing that a rumour, or a joke, began to run through the crowd: people were being so drawn in by these on-screen cons that they were being pickpocketed, again, in real life.

*

‘This book was meant to be the first volume of the autobiography of Dugmore Boetie. Now I don’t know what it is’ – In an afterword to Familiarity is the Kingdom of the Lost (1969), its editor and co-creator Barney Simon strikes a complex note of fondness, confusion and exasperation. Giving an account of working with (and financially supporting) ‘Duggie’ in the last two years of his life, the piece is a frank and unflinching account of narrative collaboration across the ‘colour bar’. Writer and theatre-maker Simon pays tribute to Boetie as both irrepressible story-teller and friend, but also as inveterate liar and scam artist: ‘Duggie was essentially a con man, so that attempts I have made to establish the facts of his life have led only to chaos and contradiction’.

Their relationship emerged from a non-racial theatre improvisation group that Simon was running in 1960s Johannesburg, one that ‘attempted to investigate, through improvisation and monologues, the everyday encounters between us. Not the dramatic ones; the seemingly simple ones, where the convolutions were as complex, the poisons as insidious’. Boetie was a ‘vital and voluble’ member of the workshops: ‘His stream of anecdotes was endless’. Though Nat Nakasa, who had published some of Boetie’s writing, warned Simon (and other enthralled, white members of the group) that such stories were ‘merely apocrypha of the townships’, rejigged by Dugmore to place himself in a starring role. ‘Nor did Dugmore take himself seriously’, wrote Es’kia Mphahlele about this dubious autofiction in The African Image: ‘He establishes in one’s mind a “Dugmorean” way of life, as if he were at the helm of things’.

Even while half suspecting that he was being taken in (part of the strange psychic architecture of the confidence trick: you always half-know you are being duped, you collaborate in your own humiliation), Simon worked with Boetie for the next two years, supporting him financially and slowly drawing out of him enough material for a book. It appeared only after its protagonist had succumbed to lung cancer – an ordeal that Simon becomes deeply and sometimes uncomfortably involved in. During his visits to Boetie in hospital, it slowly emerges that this supposed autobiographer has fabricated all the most important plot points of his life: among them the grisly death of a tyrannical mother in the opening lines of the book (she eventually appears, as a sweet old woman, at Duggie’s deathbed). And also the loss of his leg, which happened when he was a child, not when heroically fighting Rommel in North Africa. Simon’s deeply felt essay registers both the intimacy and contempt bred by Familiarity – a book which could be described both an act of sincere and deeply felt narrative collaboration but also a project of mutual, long-term duplicity with many flash points:

Now I knew the score. The lies. The cons. Those hospital trips to the ‘loner’. Even the money for the old woman hadn’t reached her. But he was there. On my back. For the rest of his life at least. I hated him. He hated me. I just wanted to walk out, to be left alone.

Boetie’s work was widely read and reviewed internationally when first published, its scrambled codes of first person confession, pulp fiction and gangster thriller allowing it to circulate within South Africa when so many other black autobiographies of the time were banned. But today it is largely forgotten, or regarded as something like the joker in the pack of Sophiatown-era life writing. ‘Three reasons, I suspect, have concurred to silence Dugmore Boetie’, wrote Mark Beittel in Staffrider magazine: ‘doubts about authorship, discomfort with its form and suspicions about its politics’.

Rather than providing the kind of usable testimony and solidarity expected of apartheid autobiography and political prison writing, Familiarity enacts ‘a literary con’ (as one reviewer put it) in multiple senses. It is firstly the picaresque account of Boetie’s life as thief, confidence trickster and convict: a rollicking and often very funny narrative of its one-legged subject’s adventures as scam artist in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Durban. The narrator takes the reader through an encyclopaedic catalogue of rip-offs, swindles and hoaxes, often pandering to the prejudices of white South Africans in order to dupe them, or else matching the absurdities of apartheid bureaucracy with the narrator’s own surreal gambits.

In ‘The Last Leg’, first published by Nakasa in The Classic, Boetie is sent to prison and demands to check in his prosthetic limb as a personal effect, so as not to have it worn out during his time doing time. It has, he insists, been given to him by well-meaning social workers, and is far above the standard of government-issue (wooden) legs for black patients. So he insists, despite beatings from the exasperated warders, that it should be preserved in storage until the end of his sentence, as one of his personal effects. It is a request that wreaks comic havoc with the bureaucratic order of the prison, and joins several other Drum-era writers in sending up the farcical legalism of apartheid thinking – apartheid as, in Lewis Nkosi’s words, ‘a daily exercise in the absurd’:

‘This is beyond me. I looked it up in all the prison rule books but I can’t find anything that says that this convict is not right’.

‘Why shouldn’t he use it in prison like he used it in that stolen car?’

‘Wrong!’ I thought. ‘My artificial leg is innocent. It was Tiny’s leg that was supposed to press in the clutch.’

When Dugmore is out of prison and at large, the reader is taken into the subcultural lore and lingo of whole range of petty crime and racketeering – railyard theft, bootleg liquor, number running. In one passage, the narrator explains the technique of ‘square-hunting’:

The jolter will jolt, she’ll look up to be met by a ‘Sorry, madam’. This gives the ‘can-opener’ a chance to unbuckle the bag. At the same time the square-puller will come in between them and lift the square. We never miss, because there’s no stopping, no hesitating, no pausing, it’s just one smooth movement. Clear, straight and neat.

But, as with the screens on Long Street, the action here might be part of a larger confidence trick being played on anyone who is actually taking such scenes seriously. Dugmore’s accomplice Tiny, we read, ‘went about it with an elastic sense of humour’:

He once pinched a purse and, finding it empty, walked up to the victim and said: ‘Lady, here’s your purse. Next time don’t decorate the inside of your bag with an empty purse – keep something in it. Think of all the risks I have to take.’

As a yarning ex-convict and teller of tall stories who has strayed into the genre of autobiography, Boetie calls to mind a work by another very literary con, Herman Charles Bosman. Cold Stone Jug (1949), Bosman’s account of serving time (and narrowly evading the gallows) in Pretoria Central for shooting his stepbrother is full of traps and tricks for the unwary. This strand of prison writing also winds through the accounts of Pollsmoor’s gangs in Breyten Breytenbach’s The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (1984) and Jonny Steinberg’s The Number (2004), where the author knows himself to be in the hands of some of the Western Cape’s ‘master bullshit artists’ and worries about tying himself to a biographical subject, Magadien Wentzel, who might be nothing more than a ‘sophisticated trickster’. ‘Touch a man lie that anywhere’, Steinberg writes, quoting Bosman, ‘and stories would flow from him like blood from a wound’.

Drawn to the arcane narratives of ‘non-political’ (i.e. common-law) prisoners, these literary cons are experimental outliers within the genre of the South African prison book. They form a counter-tradition to the many anti-apartheid autobiographies that seek to build needful solidarity and an archive of testimonial data. They also trouble the divide between criminality and political resistance within an unjust society – a zone of constant ambiguity and ideological anxiety within many Struggle memoirs (and the TRC itself). In telling the self-mythologising stories of Wentzel and other gang members, Steinberg must sift through the self-conscious performance and even deliberate duplicity of compulsive storytellers who want their wisdom affirmed but are nonetheless wary of releasing too much of the information that their community holds in trust, or spending their narrative capital too quickly.

It is in these kind of psychological domains – a social scene irredeemably warped by reciprocal stereotypes and racial caricatures; an interpersonal encounter where ‘culturally activated transferences are easily traded for truth’ in N. Chabani Manganyi’s deft phrase – that Dugmore’s con tricks operate, albeit in a lighter, more irresponsible mood. The Dugmorean hoax plays within the dynamics of mutual self-deception, ironic accommodation and (in Homi Bhabha’s phrase) ‘sly civility’ that pass between black and white. Such dynamics are recorded with lacerating frankness in the very different mood of Bloke Modisane’s Blame Me on History (1969) – a work that appeared in the same year as Familiarity but is trapped in a syndrome of doomed liberal humanism and confessive but corrosive ‘honesty’ that Boetie’s narrator has taken for all it was worth, then gleefully abandoned.

Not that we aren’t given fair warning, as several scenes send up the whole act of reading itself. At one point, his accomplice distracts a white worker in the railyards by asking him to read something for him: a failsafe way to buy time because the victim cannot admit that he is illiterate. The street philosopher Boetie goes on to give a clue to his cryptic title:

The white man of South Africa suffers from a defect which can be easily termed limited intelligence […] I say this because no man, no matter how dense, will allow himself to be taken in twice by the same trick. They don’t learn from their mistakes, for the simple reason that they’d rather die than talk about their mistakes. Me, I learn by my mistakes because human beings make mistakes, and I’m a human being. Their pride is based on colour, and it’s on this pride that we blacks feed ourselves. Call him ‘Baas’ and he’ll break an arm to help you.

He takes advantage of his white skin, we take advantage of his crownless kingdom.

Finally, the entire book might best be described as an elaborately rigged confidence trick, a meta-textual con at the expense of the politically correct, well-meaning reader looking for an indictment of social ills. In one scene, Duggie steals a roll of bank notes left on the counter, tosses it to an accomplice outside and then decides to wait for his change. When the police automatically assume he is guilty and start beating him up, his cause is taken up by another customer, a white woman, waiting in line. ‘The way she went on, it was as if she was suffering more than I was. A lovely bundle of fury’:

‘Tell me now,’ she was almost begging, ‘do you for one minute think that if anyone could steal a roll of pounds he’d be so stupid as to stand and wait for a measly fourpence change when the door was wide open and he had every chance of running away? I,’ she spat, ‘would give everything I possess – and I can assure you it’s considerable –’ (Chancer, I thought) ‘if that boy is guilty of theft.’ I stole a glance at the other customers and saw most of them nodding their heads in agreement.

This mood of ironic, unstable and sometimes painful comedy permeates not just the book but also the larger story of how it came to be. Dugmore’s family begin to suspect Simon of trying to scam them in turn, as the all-too-familiar figure of a white man conning black folks out of their cultural heritage for profit. The afterword culminates in an awkward haggling scene over which kind of coffin should be purchased for Dugmore’s funeral, itself an event which is a far from satisfactory end to things:

Afterwards I went to shake hands with Duggie’s mother. There was tension. I tried to mention the manuscript papers to his sister. She looked blank. As we began to get into my car, a young man came up to me. He was asking, he said, for all the family, about the money from Duggie’s writing that was sold in London. Car doors were slamming all around. There was dust. It was too hot. I just stopped talking. Perhaps this was Duggie’s final con.

I knew that it would be a long time before I got the papers back. It was.

Johannesburg, 1968.