![Matching Shadows]()

Landscape, photography, environmental memory.

Remembering the Plant Conservation Unit. Business Day, 14 September 2021.

Safundi 22 (2022). Roundtable on University of Cape Town fire of April 2021.

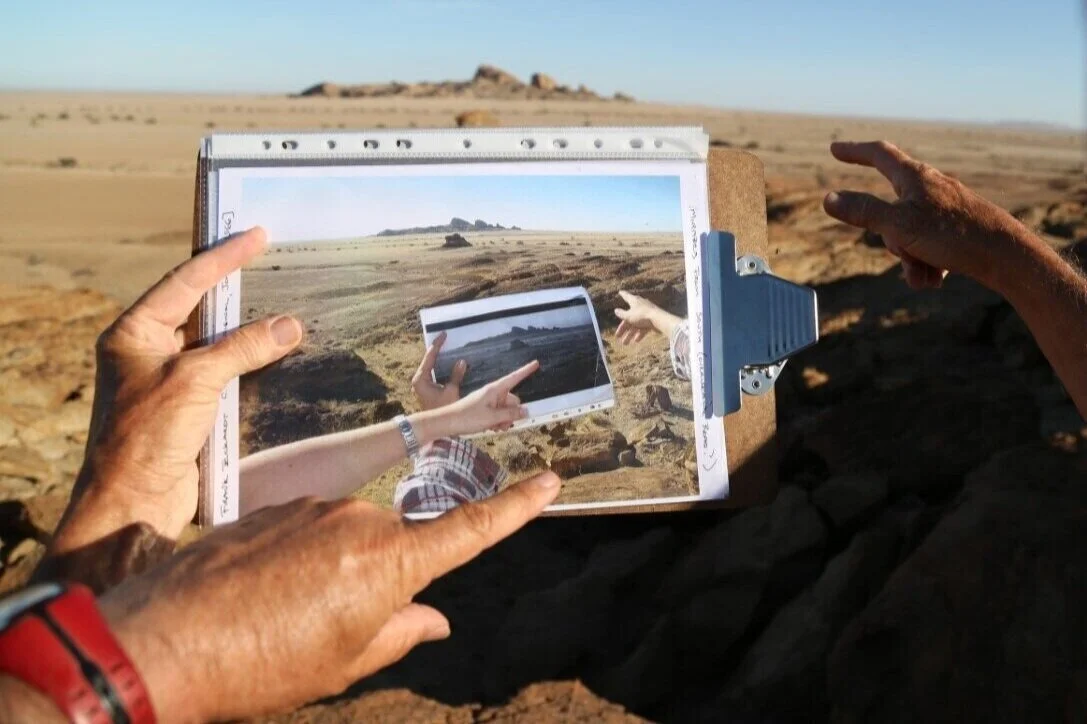

A photo within a photo within a photo: the Mirabib inselberg in the Namib Desert. The innermost image is from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which featured this landscape during the opening sequences (Kubrick's team also cut down several ancient kokerbooms, illegally, since he was fascinated by the tree and had plastic models made for the film).

I wrote about the repeat photography project run by Timm Hoffman and the University of Cape Town’s Plant Conservation Unit, which burned down earlier this year. (It wasn't the first conflagration they've had to endure. In 2016, the PCU's Mazda bakkie was set alight during protests, a vehicle that had taken students all around the country, and linked the university to a remote Namaqualand town for over 20 years. But that, as they say, is another story.)

The physical pictures, plates and negatives may have burned, but over 30 000 images exist on the digital database. And so the invitation to be part of the project, to find these sites and re-take the photos, lives on in virtual space.

Read More

![Dirty Butter]()

Artificial Selection by Elize Vossgätter.

Catalogue essay, August 2021. Everard Read gallery, Cape Town.

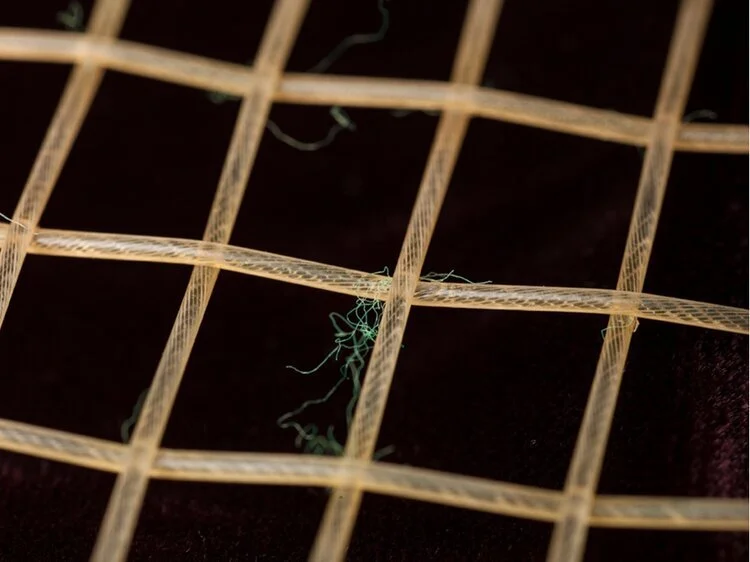

In 1880, a German pharmacist named George Grübler started a business in Leipzig, manufacturing a dye called gentian violet. The name came from the Gentiana, a genus of flowering plants with petals ranging from deep blue through indigo to the end of the spectrum; but the colour was entirely synthetic.

Gentian violet was one of the aniline dyes that emerged in quick succession after the discovery of mauveine in the mid-19th century. Colour was denaturalised, industrialised: no longer just a precious pigment extracted from the natural world, but now also something mass-produced by chemists fiddling with molecules, and sold by the tonne to the garment industry. Grübler sold his dye mainly to biologists for histological staining: i.e. to stain cell walls, organelles and chromosomes, so as to probe their microscopic structure. Gentian violet was used by early geneticists and the cancer researchers who developed chemotherapy. Today it remains vital in the classification of bacteria, producing slides stippled with pink and purplish specks.

Using artificial colour to render complex or intractable natural structures: not dissimilar to the way climatologists code weather maps (with new shades of violet for unprecedented heat waves as we move further into the Anthropocene). Or, at the other end of the scale, the way astronomers picture impossibly distant phenomena via ‘false colour’ images. Arbitrary palettes are assigned to encode intensities and wavelengths lying outside human apprehension – the ultraviolets and distant radio galaxies that show up as tiny flecks or blurry chromosomes.

Read More

![Prince Pro]()

About my father's record collection and my mother's tennis racket.

In Object Relations: Essays and Images. Edited and photographed by Stephen Inggs. Michaelis School of Fine Art, 2014.

When I was 18 and finishing school abroad, my father went (I think) a little crazy. He began giving away all our things. This is, perhaps, understandable behaviour when you are retrenched from a company you never liked anyway, and then move to the opposite side of the country. But still, the scale of the purge stunned me.

First, the record collection. My father was at Leeds University during the 1960s, and often let it slip that Clapton, Hendrix and The Who had played in the student union, that it was no big thing back then. He had all their albums, with that luxuriant amount of space the LP format affords for artwork. Roger Daltrey in a tub full of Heinz baked beans (The Who Sell Out) and Carole King just kicking back at home with her cat (Tapestry). The original of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band itself, complete with cardboard insert epaulettes and moustaches that you could anchor in your nose via little tags. The naked, languorous women spread over the gatefold cover of Electric Ladyland – for a small boy on a mining town on the far West Rand in the dying days of apartheid, this was a formative document.

And when the needle came down, the low-end kick of these records on an analogue stereo: Eddie Cochran's Summertime Blues, Simon and Garfunkel's Cecilia. It sent me into paroxysms of excitement.

Read More

![The Life of the Mine]()

Remembering Nadine Gordimer (1923-2014)

Business Day, 22 July 2014.

‘Responsibility’, wrote Nadine Gordimer in one of her most important essays, ‘is what awaits outside the Eden of creativity’. As the many tributes to her over the last week have shown, this was a writer who took such responsibilities seriously. Always ready to be in the intellectual thick of it – whether involved with the ANC-aligned Congress of South African Writers during the struggle, or opposing ANC-led bills limiting public access to information toward the end of her life – Gordimer was a model citizen of the Republic of Letters if ever there was one. The move from ‘creative self-absorption’ to ‘conscionable awareness’ is the essential gesture that gives the essay its title and the oeuvre its extraordinary social and historical breadth.

But what about the second half of that sentence? What was unique, strange and private about her work? What exactly was the nature of that enclosed and fertile space – ‘the Eden of creativity’ – that made her the writer she was?

Read More