![The Sound of Islay]()

Introducing the Bodley Head / FT essay competition.

Financial Times | 11 November 2016.

1.

Just before I turned 30 I was homeless for a while. Homeless is the wrong word, an exaggeration. But I was in Edinburgh with little money and nowhere to live – and the days were getting shorter. So I took myself off to the Scottish islands with a bike and two red waterproof panniers. The plan was to stay in bothies – stone cottages that shelter hikers and climbers, remote structures in the hills where you just arrive and take your chances.

I started in Oban on the west coast, then pedalled south to the ferry port on Loch Tarbert – one of the long fingers of ocean that reach deep and diagonally into Argyll. This was a mistake, since there was too much traffic on the mainland. Massive cold fronts broke in off the Atlantic, one after the other. I tried to cycle in the lulls between showers but was soaked through my Gore-Tex by rain and truck spray. I found myself unable not to take the headwind personally. I would burst regularly into tears on the hard shoulder – homeless, jobless, indebted and drenched.

Things improved when I boarded the ferry to Islay (pronounced Eye-La). A couple bought me lunch because I fixed their punctures. All us cyclists rolled off the boat ahead of the vehicles – we would encounter each other at different jetties and pubs and bunkhouses all through the isles: instant camaraderie. I visited distilleries and hiked to a bothy in a remote cove. The cottage was full of other people’s leavings: oatcakes and freshly cut peat in a creel, shiny cutlery and coffee pots all arranged there like the Marie Celeste. I half-expected a party of spectral hill walkers to come back any minute, but no one ever did. It was just me, myself and I – pinned down by (another) frightening Atlantic storm for three days and three nights.

When it subsided, I crossed to Jura: a wilder, emptier place where you must constantly check yourself for ticks, since the island is full of deer. Jura is also (I learned) the place where George Orwell lived in a remote cottage towards the end of his life, where he had written Nineteen Eighty-Four, and worked on the memoir ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’. This triumphantly miserable piece about his schooldays is one of my favourite pieces of non-fictional prose – and I have always taken it as significant that this was the essay he was revising on his deathbed. Orwell would come here to retreat from literary London, and was once almost drowned in the famous whirlpool of Corryvreckan off Jura’s north coast. You could hear its thunderous sound from where I camped – boulders being stirred on the ocean bed, like the long, drawn-out roar of a passing plane.

Read More

![The Institute for the Less Good Idea]()

Visiting William Kentridge at his Johannesburg studio.

Financial Times magazine, 2 September 2016. PDF.

My (longer) edit, with The Nose reinstated:

I knew I was at the right place because of the cats. Two sculpted, spiky creatures faced each other atop the gates in Houghton, one of Johannesburg’s wealthy, jacaranda-shrouded suburbs. I recognized them from drawings, etchings and films – in which cats emerge from radios (Ubu Tells the Truth), curl into bombs (Stereoscope), turn into espresso pots (Lexicon). Now they had become metal, swinging open to reveal a steep driveway and above it a brick and glass building perched on stilts amid foliage: the studio. A gardener directed me past some cycads to the right entrance and there an assistant ushered me in to meet William Kentridge. He was wearing a blue rather than a white collared shirt, but in all other aspects conformed to his self-appointed uniform: black trousers, black shoes, the string of a pince-nez knotted through a button hole, the lenses stowed in a breast pocket when they were not on his nose.

Read MoreA walk through South Africa's nuclear pasts and futures.

Sunday Times, 7 Feb 2016. Sunday Times article PDF [1/2] | [3]

Photographs by Neil Overy (above) and Barry Christianson.

Recently I took part in a ‘walking residency’, making my way from Cape Point to the centre of Cape Town. Writers, artists, archaeologists, architects, academics - 12 of us hiked along coastlines and firebreaks and through informal settlements.

We visited ancient shell middens and ruined stone cottages, the site of forced removals. Huge cloudbanks filled up False Bay and broke against the landmass; weather systems came and went. We got sunburnt, argumentative, sentimental, sunburnt again. We put away our electronic devices and began remembering our dreams ...

Half-lives, Half Truths. Svetlana Alexievich and the nuclear imagination, South Africa PEN essay series, 18 August 2016. Republished in Firepool.

Read MoreA journey through the public pools of greater Cape Town.

Openings column | Financial Times, 8 January, 2016.

Waterlog #3 | Sea Point Pool | 19.01.16

Since Silvermine there have been terrible heat waves; fires leaving smoke all over the city’s horizon; helicopters toiling through the night, scooping up water from the reservoirs, dropping it in tiny white plumes on the shoulder of Devils’ Peak.

A banner appeared, taking up the whole face of an apartment building at the top of Long Street: Zuma Must Fall. Then an ANC-led march ripped it down, turning on a man who (allegedly) called out Zuma se ma se poes! On social media, self-appointed pundits explain that singling out the President is tantamount to racism, and that mob violence is only to be expected. People can only be insulted for so long.

Can you blame a man for wanting to go to the water?

Read More

![MER1CA]()

On first impressions, snap judgements and Achille Mbembe's sense of style.

Openings column (shorter version): Financial Times, 14 August 2015.

‘America is the most grandiose experiment that the world has yet seen,’ wrote Sigmund Freud in 1909, ‘but, I am afraid, it will not be a success’. 106 years later I spotted the line on a poster while attending a conference at New York University – my first visit to the States. It cheered me up during a misanthropic, jet-lagged daze and set off a complex series of recognitions. For one thing, I had been thinking along the same lines myself, and marshalling every scrap of evidence to clinch the case: the bad coffee at four dollars a pop; the garbage everywhere; the fact that I got asked to move out the way at least five times a day.

But at another level, what I responded to was the tone: the sweeping confidence of the declaration, with that magisterial throwaway clause – ‘I am afraid’. How this Mittel-European sentence stoops down from on high, taking its time (four commas), to deliver a vast, over-reaching social diagnosis on an entire continent. This, I realized, was a voice that I recognize from people coming to my country and making huge pronouncements on South Africa – or just ‘Africa’ – when they have barely stepped off the plane. A short taxi ride from Cape Town International to the guesthouse and already they are experts.

Read MoreRereading Ivan Vladislavić: The Restless Supermarket and Double Negative.

(Much) shorter version at the New Statesman, 9 January 2015: Lost in Joburg: One of South Africa's most accomplished prose stylists gets a timely reissue.

Do copy-editors still use their time-honoured signs: the confident slashes, STETs and arrowheads, the fallen-down S that means transpose? Or is everything now done via the garish bubbles of MS Word Track changes?

Midway through Ivan Vladislavić’s 2001 novel The Restless Supermarket, the proudly anachronistic narrator Aubrey Tearle gives a disquisition on the delete mark. As a retired proofreader, regular writer of letters to the editor, and grumpy but occasionally endearing old man, he suggests that of all his erstwhile profession’s charms, this is the most beautiful and mysterious:

Read More

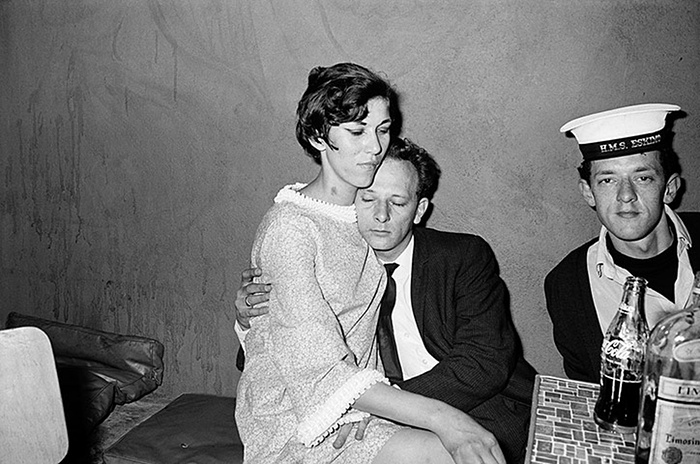

![I and I]()

Meeting Geoff Dyer.

Edited version published in the Mail&Guardian, 23 December 2014.

Can I use ‘I’ in my essays? The question, often asked by first-year literature students, isolates the problem succinctly. The first I in the sentence means me, the special, singular, irreplaceable self; the second is a devious linguistic particle: a shifty, worn-out pronoun forced on us all the moment we enter language. And the perilous thing about book festivals is that they tend to collapse the two. The I who has been flown out to Cape Town and given a name-tag is now asked to answer for, or ‘speak to’, the I on the page.

In this case, Geoff Dyer, with whom I sat chatting during the Open Book festival in September this year while we waited for a panel on ‘The Art of the Essay’ to begin – a bit like TV newsreaders used to before or after the bulletin. I told him that he was one of only two people I had ever written a fan letter to (the other was Terry Pratchett, but I was ten years old then). I asked him if he actually enjoyed going to literary festivals, being interviewed, the whole scene. ‘I can honestly say’, he replied, ‘that the only reason I write any more is to be invited to literary festivals’.

Read More