William Dicey’s 1986 (and other ‘year-books’).

Business Day , 4 May 2021.

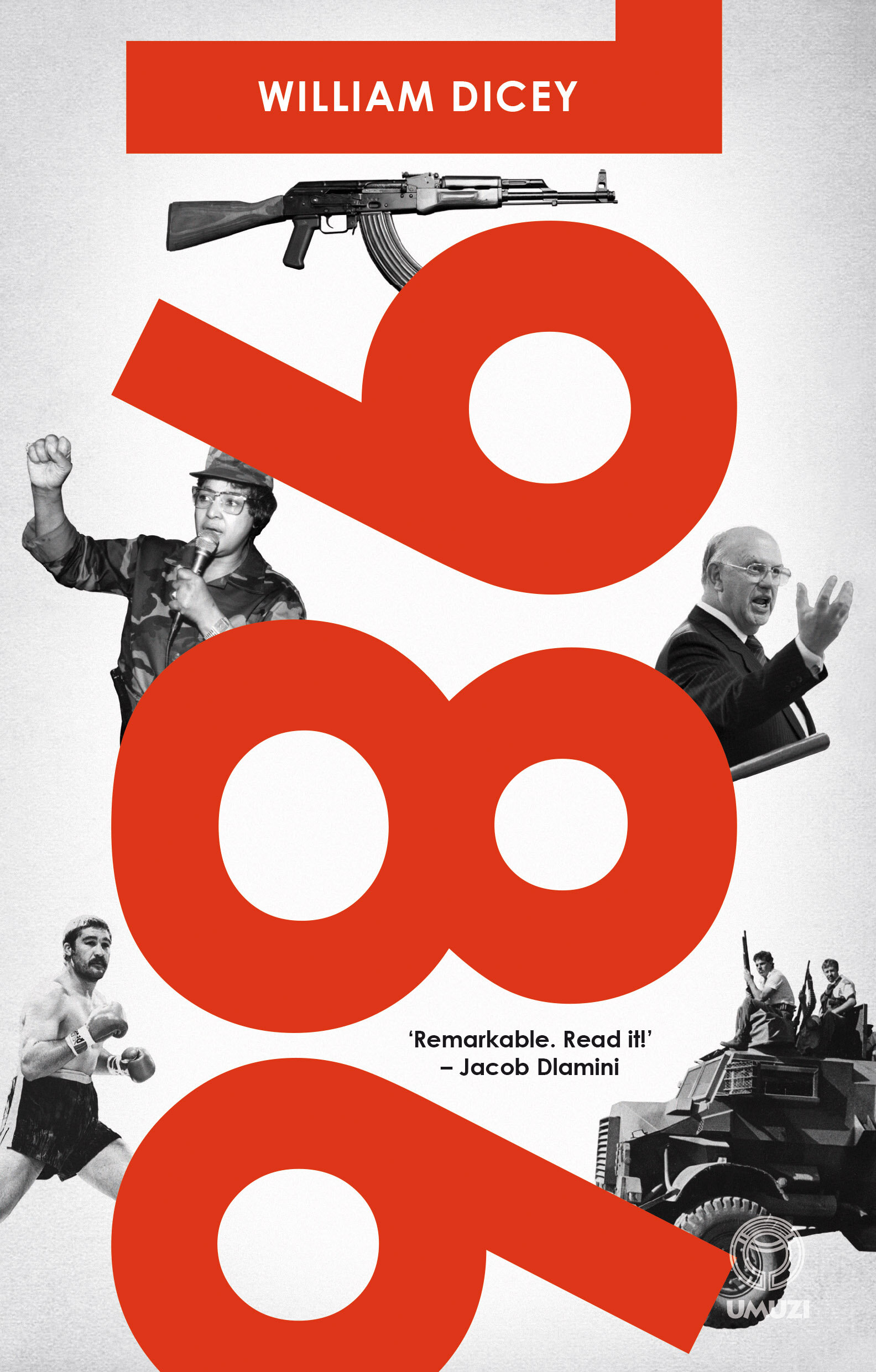

In 1986, Halley’s Comet reached perihelion, its point closest to the sun, for the first time since 1910. The Challenger Space Shuttle exploded, and so did a reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear plant. Mozambiquan President Samora Machel died in a suspicious air crash and Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme was gunned down in Stockholm. Diego Maradona scored his ‘Hand of God’ goal against England in the 1986 football World Cup.

At the 27th Congress of the Communist Party in Moscow, Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the keywords of his mandate: ‘Glasnost’ and ‘Perestroika’. The African National Congress in exile could no longer count on the same level of Soviet support – in 1985, the shopping list had run to 60 cars, 6 buses, 240 tons of soap, 16 000 tubes of toothpaste and 4000 brassieres.

Within South Africa, 1986 was the year of the people’s war, rolling mass action and rebellion in the townships. As the ten-year anniversary of the Soweto Uprising approached, P. W. Botha declared a nationwide State of Emergency on 12 June – for many the darkest hour of the anti-apartheid struggle. 1986 was the year of the Delmas Four and the Gugulethu Seven, of the Six Day War in Alexandra and the Magoo’s Bar bombing in Durban. The pass laws were abolished and the Dutch Reformed Church began accepting worshippers of all races. The South African Defence Force intensified cross-border raids, promised military training to Mangosuthu Buthelezi’s Zulu nationalist organisation Inkatha and founded the Civil Cooperation Bureau – in reality a death squad.

Winnie Mandela gave her infamous necklacing speech, and apartheid spy Craig Williamson ensured the footage was shown wherever Oliver Tambo held a press conference. ‘When the Going Gets Tough’ by Billy Ocean topped the international charts; on the local billboard it was Sipho Hotstix Mabuse with ‘Let’s Get it On’. Shaka Zulu and Knight Rider screened on TV. Paul Simon violated the cultural boycott by recording Graceland. Musician-activist Steven van Zandt (later Tony Soprano’s right-hand man) stepped up his ‘I Ain’t Gonna Play Sun City’ campaign, but advised the Azanian People’s Organisation to take Simon off their hit list: ‘The war I’m about to fight it a tricky one in the media…It’s not going to help if you assassinate Paul Simon, okay?’ Eugene Terre-Blanche, leader of the white supremacist AWB, told reporters that his open-handed salute was an old German greeting meaning ‘I come in peace’: ‘How can I help it if Hitler also used it?’

On 1 April, the British satirical show Spitting Image aired the song ‘I’ve Never Met a Nice South African’, which opened with a Botha puppet addressing a crowd of supporters: ‘My fellow South Africans, I feel it is time for me to tell you the facts as they really are: 1) Bananas are marsupials 2) Cars run on gravy 3) Salmon live in trees and eat pencils 4) Reform in South Africa is on the way.’

These are just some of the things you learn in William Dicey’s 1986, a richly researched, carefully arranged portrait of late-apartheid South Africa in all its cruelty and violence, absurdity and hope. The book adopts a beautifully simple structure – moving chronologically through the year, with each month forming a chapter – to reflect on a chaotic and contradictory time. ‘It was a watershed’, says Dicey in interview, ‘the last year in which a civil war seemed a distinct possibility. By 1987, a negotiated settlement looked more likely. It was a very violent year – vigilantism peaked, necklacing peaked – but it was also the year the talking began, by which I mean meaningful talking between the government and the ANC’.

The book closes on 24 December 1986, Christmas Eve, with Nelson Mandela being taken for a scenic drive by the deputy commander of Pollsmoor. The most famous political prisoner in the world rides secretly along the Cape Peninsula coastal road from Hout Bay to Sea Point. ‘It was absolutely riveting’, Mandela writes in his autobiography, ‘to watch the simple activities of people out in the world: old men sitting in the sun, women doing their shopping, people walking their dogs. It is precisely those mundane activities of daily life that one misses most in prison.’ It was the first time Mandela had observed civilian life in twenty-two years, and Dicey gives him the last line: ‘Though the country was in upheaval and the townships were on the brink of open warfare, white life went on placidly and undisturbed.’

*

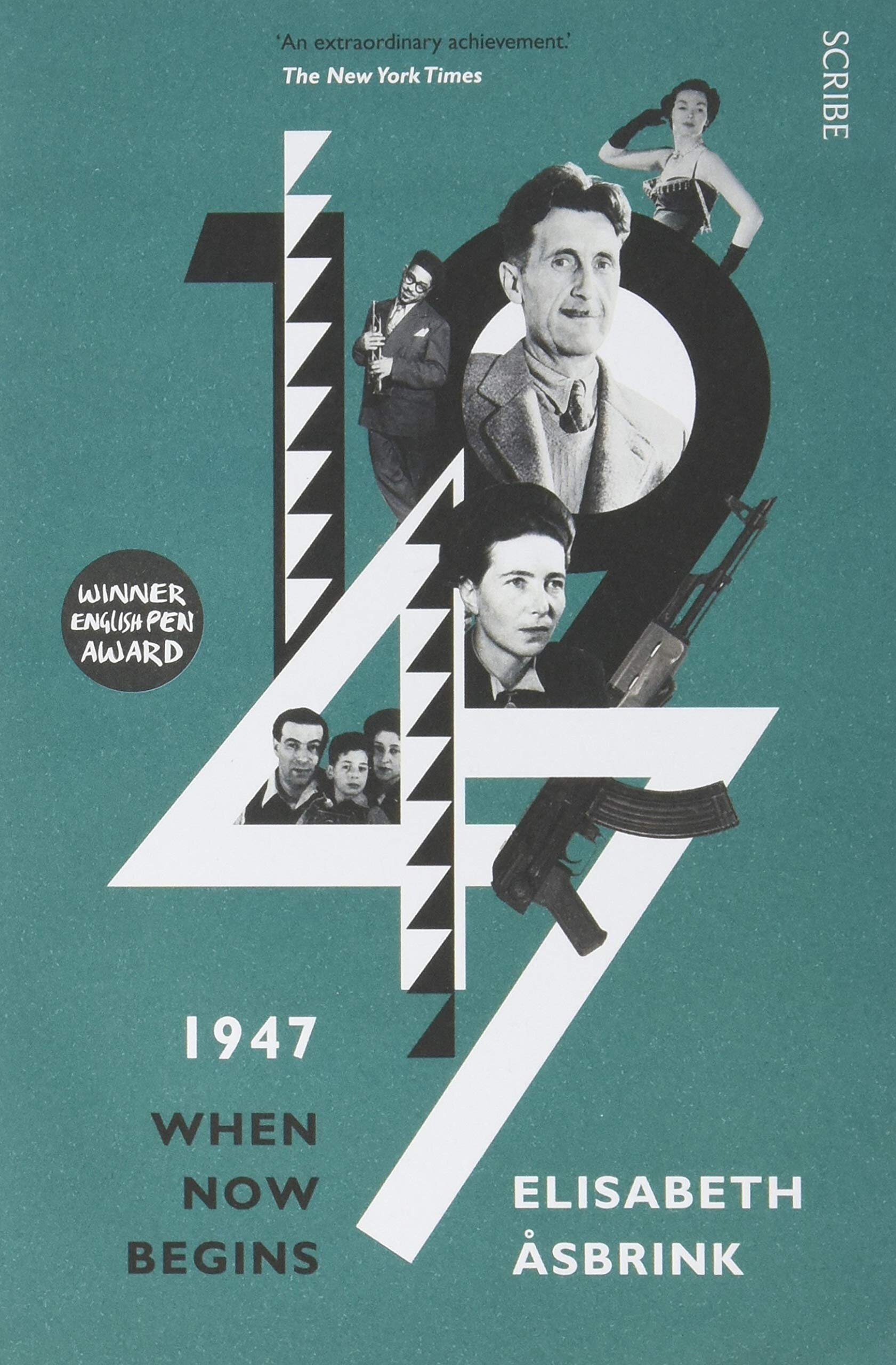

1986 joins what is by now a global sub-canon of books tied to specific years. There is Florian Illies’s 1913, a portrait of European modernism just before the catastrophe of the First World War (Kafka writing love letters in Prague, Stravinsky composing The Rite of Spring in Paris, Hitler failing as an artist in Munich). And there is Elizabeth Asbrink’s 1947, subtitled ‘When Now Begins’: the modern world order taking shape in the aftermath of World War Two. This was the year of The Second Sex, the founding of the CIA, Partition in India and the UN Committee’s failed mission to Palestine (it was also when a dying George Orwell wrote the most famous of all ‘year-books’, Nineteen Eighty-Four, on the wild Scottish island of Jura).

The method has been used biographically. James Shapiro’s 1599 focuses on a year in the life of Shakespeare, trying to understand how he transforms from being just a very good playwright to the artist who wrote four of his greatest works, Hamlet included, in only twelve months. Sometimes year-books are tied to weighty colonial or world-historical markers, like Patric Tariq Mellet’s The Lie of 1652 or Charles C. Mann’s tantalising 1491.

And sometimes the opposite, when a much more ‘ordinary’ moment in time is selected, and a virtue is made of its arbitrariness. James Joyce’s Ulysses takes place on 16 June 1904, now celebrated as ‘Bloomsday’ by literary pilgrims retracing the steps of the fictional Leopold Bloom in Dublin. A non-fictional variant is Gene Weingarten’s One Day, in which the American journalist asked three people to pluck day, month and year out of a hat – and then worked with this random selection: 28 December 1986.

‘He was disappointed’, Dicey told me, citing the book as one of his inspirations, ‘Because it was a Sunday, a slow news day, between Christmas and New Year. But what he did with that day, that one random day in America, is remarkable’.

Dicey’s treatment of 1986 in South Africa works with both national history and private experience. Its brisk, self-contained entries constantly tack between the newsworthy and the mundane, the instantly recognisable and the largely unremembered. The rigid guiding concept – sifting and reporting what happened from day to day in 1986 in South Africa, with little comment or analysis – allows the book a curious freedom.

It makes 1986 unpredictable. We shift scales, locations, even genres from entry to entry. On 28 February we are plunged into the assassination of Palme, still one of the largest unsolved criminal cases in world history (but almost certainly involving South African agents who opposed his support for the ANC). A few pages later, the writer Bloke Modisane dies on 1 March, and we are pulled into the world of 1950s memoir and literary history, the strict calendar format becoming entangled with other times and pasts.

‘It was obviously an accident of history that Modisane died in 1986, after twenty-plus years in exile’, Dicey comments, ‘But it allowed me to talk a bit about the politics of the Fifties, which obviously enriches one’s understanding of the Eighties. I also talk about Modisane’s everyday life – or, rather, I let him talk about it, by quoting from his memoir Blame Me on History. An early reader called my book a collection of voices. I liked this comment as it drew attention to one of my objectives: to get a range of different people to describe their experiences of life under an authoritarian regime.’

The central constraint also works to head off some literary clichés and common pitfalls. For example: were you alive in 1986? And if so, where? What were you doing, or thinking? What do you remember? These are the kind of questions that the title prompts; it invites personal reminiscence, anecdote, family history. I’m immediately tempted to tell you about starting at a government primary school with posters of Communist limpet mines on the walls and that time when… – but this is exactly what the author does not allow himself.

‘Self-description is, like rugby, a national pastime’, writes Vincent Crapanzano in Waiting, an ethnography of 1980s white South Africa. The author remarks how much his subjects, in being unable to imagine a viable future, tended to talk about themselves instead. The point about talk and double talk is also made in foreign correspondent Joseph Lelyveld’s account of the same period, Move Your Shadow: ‘A lot of words get spilled as the urge to be understood clashes with an aversion to being understood too well.’

Both of these psychologically acute works of non-fiction from 1985 underlie 1986, and one senses that Dicey has absorbed some their lessons, and their wry, restrained sensibilities. His previous books comprise a memoir of kayaking down the Orange River, Borderline (2004) and a collection of personal essays, Mongrel (2016), in which the standout piece was, for me, a laceratingly frank account of what it means to run a fruit farm in the Boland (complete with financial spread sheets). But in 1986, the explicitly personal voice – or the companionable, guiding intelligence of the essayist – is largely absent.

There is no preface or preparation for how to read the book. 1 January plunges us into a vigilante attack in a town near the ‘homeland’ of KwaNdebele. On New Year’s Day, henchmen of Simon Skosana, KwaNdebele’s chief minister, abducted and tortured local residents who opposed the incorporation of their village into his ‘self-governing’ fiefdom. It is an obscure, largely forgotten episode that shows how the method works to unearth awkward, inappropriate elements of the past.

In the afterword, there is a brief mention of the author’s being at high school in 1986, and realising what one of his rugby team mates, Thobile, was going through in moving between Gugulethu and the white suburbs: ‘On weekends, he’d have to change into civvies before catching a taxi home. Had he showed up in Gugs in blazer and boater he’d have been attacked.’ But this initial idea (which would have become, Dicey suggests, an overworked story of friendship across a racial divides) was abandoned for a clipped, reportorial style and a much wider angle of vision. The prose is stripped, informational, unsentimental – as if on guard against the nostalgia, justification or sheer self-centredness that personal memoir is prone to.

*

Approaching late-apartheid South Africa via a rule-based, strictly governed process is also apt in another sense. In his book on the conceptual artist Willem Boshoff, Ivan Vladislavic describes the regime’s legal and bureaucratic contortions as resembling ‘a grotesque conceptual game’: ‘The doubling, trebling, quadrupling of institutions and facilities along racial lines, the obsessive categorisation by race in the law, the establishment of tinpot homelands, all these elaborations were so grandiose that it was scarcely necessary to comment on them, they simply needed to be framed.’

In a sense, 1986 is a conceptual writing project that works to frame the enormity and absurdity of its subject – with no further comment necessary. ‘There were 14 legislative assemblies’, Dicey told me in our email Q&A, ‘With over 1200 members between them; there were 18 departments of health. At one point, KwaZulu comprised 29 separate parcels of land, Bophuthatswana and Ciskei 19 each.’

‘Life can only be understood backwards’, Søren Kierkegaard said, ‘but it must be lived forwards’. Because of what came after – the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, democratic transition and all the global media attention it garnered – there is sense in which the 1980s have been somehow foreshortened in national memory, or placed in a kind of cold storage. As a result, the feeling of what it was like to live (forwards) through that decade is doubly hard to recover. Dicey stresses that he is no historian, but his book imparts a historicity that is often lost in more standard treatments: a sense of the past as something experienced rather than understood. We come closer to the bewildering intensity and uncertainty of a present that has not yet resolved into a meaningful shape, immersed in a past where other futures are still possible.

In this way, a subtly crafted non-fiction like 1986 operates differently to the op eds and think pieces that pour out daily to fill the online world’s voracious need for ‘content’. In most content, there is very little new information or original reporting, but lots of overbearing interpretation, recycled comment and opinion. In 1986, the ratio is the opposite: a deluge of information and archival texture, but very little explicit interpretation.

‘Interpretation is what essayists do’, Dicey comments, ‘I suppose it’s what we all do. And it’s surprisingly hard to resist. But I think writers are at their most deceitful when they try to link things, as in “A then B then C”. I mean, if there aren’t any interesting connections to be made, then “A and B and C” is better. There’s no need for overreach. In prose writing, much of the dishonesty or contrivance comes in the fascia, or linking tissue.’ The result is a slow, incremental build. Bits of the puzzle are slowly assembled, but much is left to the reader by way of connection and pattern-recognition, or the drawing of wider conclusions.

‘I have always grappled with the fact that the truth cannot be packaged into one soul or one mind alone’, writes Nobel-laureate Svetlana Alexievich, whose Chernobyl Prayer also unfolds as a chorus of overlapping voices from the past: ‘It is something fragmented, there is so much to it, the truth is varied and scattered across the world.’

Adding 1986 to my growing shelf of year-books, I had a vision of a literary universe, like something from a story by Jorge Luis Borges, in which every year of human history has been written about, wonderfully, by someone (Wikipedia has already started the process). ‘We’ve got a sequence going’, said Dicey: ‘Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four; Anthony Burgess’s sequel 1985; my 1986. And I got a text from someone I know yesterday: “My mother has finished your book and is now writing 1987. She is inspired.” God help us.’